How electronic tags can support people away from crime

Gemma Fraser, Head of Restorative Justice and Recovery at Community Justice Scotland, talks about the real life stories where electronic monitoring has made a difference to people’s lives

Jack was only a teenager when he was arrested and sentenced to a second chance. Electronic monitoring – or a tag – as part of his sentence, made the world of difference in his case.

“I grabbed it. Completed my hours, tag off, working on my anger. Without this chance, I don’t know where I’d be. Who I’d be,” he explained.

“At least I got a second chance from the judge there. My life was in her hands. The right hand was jail, and the left hand was other, and I’m glad I got the left hand.”

Electronic monitoring can help change lives and reduce reoffending when it’s used with the proper support services. I’d welcome more use of it where it’s safe and appropriate for an individual’s case.

A tag could be part of a community-based sentence to restrict someone’s movement such as a curfew but can also be used to support someone in the community while on bail and also for some people when leaving prison.

This type of sentence with support services can help to reduce further offending by addressing a person’s needs and the causes of offending within a safe, managed community environment. It can support people to comply with the justice system, to attend court appointments and reduce the likelihood of breaching bail or a community-based order.

We know from the evidence that community sentences like this can work in stopping reoffending – but we also hear from individuals about the positive impacts.

Jack from Moray was 19 when he landed up in court after he says he went off the rails and got involved with drugs and alcohol.

“Being in a court by yourself for a change, is quite nervous, anxious, terrified, names getting called out, and when my name was getting called out, you have to go down to the dock. You have to go up in front of the judge, and the PF (procurator fiscal) is explaining, your solicitor’s fighting for you. It’s quite an intense time, because from the minute I was in that dock, I thought I was getting a custodial sentence,” he explained.

“Luckily, I came away, and she turned round and says, ‘I’m going to give you a Community Payback Order of 120 hours,’ and then I got a tag round my ankle for 145 days, and I also got an 18 month supervision order.

“A Community Payback Order, I think it gives you a sort of a wake-up call, and it gives you new skills as well, because you’re doing different things like painting, gardening, woodwork, removals, if you are treating it like a workplace, as I did. So in a way, I can say I enjoyed it as well, I took it as a punishment, but I benefited from it as well, gaining new skills, obviously, to help me get into work as well.

“I won’t be offending with drugs again, and I’m nae dealing whatsoever. It was a big mistake, but I feel that if I keep thinking positively, and having confidence and all that, I can have a good future, that’s where I see my life going.”

Others who have been on electronic monitoring orders have reported what it meant to them.

One man, 32, from Glasgow, said: “Being on tag has made me a better person, I don’t want to go back to my previous way of life.”

Another man, 39, from Airdrie, revealed: “I found it hard to remember my curfew at the start. I feel like I have a better schedule now, having the support of my family made it easier.”

A 35-year-old woman from Alloa said: “I’m not going to get into trouble again after this.”

A Livingston man who’s 37, commented: “Having no night life was hard, my behaviour has been calmer since being on tag. I did find it challenging to get home from work on time before my curfew started.”

How training courses run by Community Justice Scotland are helping to make a difference

David Scott, CJS’s Head of Learning, Development & Innovation reveals some of the very positive feedback received for training delivered right across Scotland

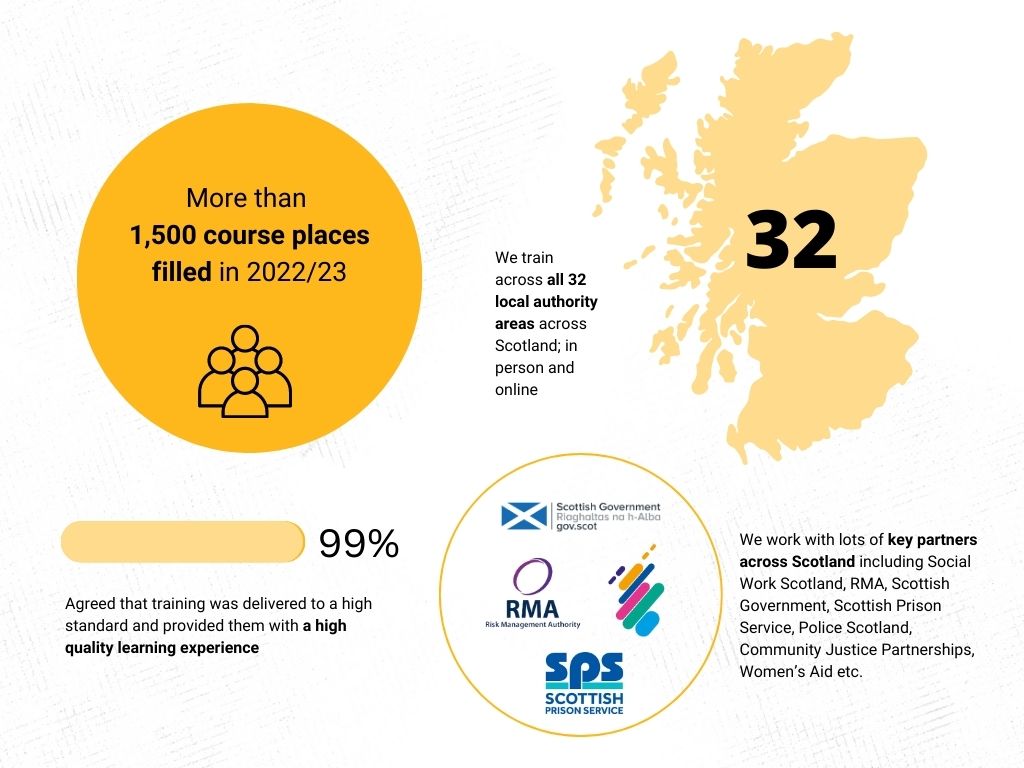

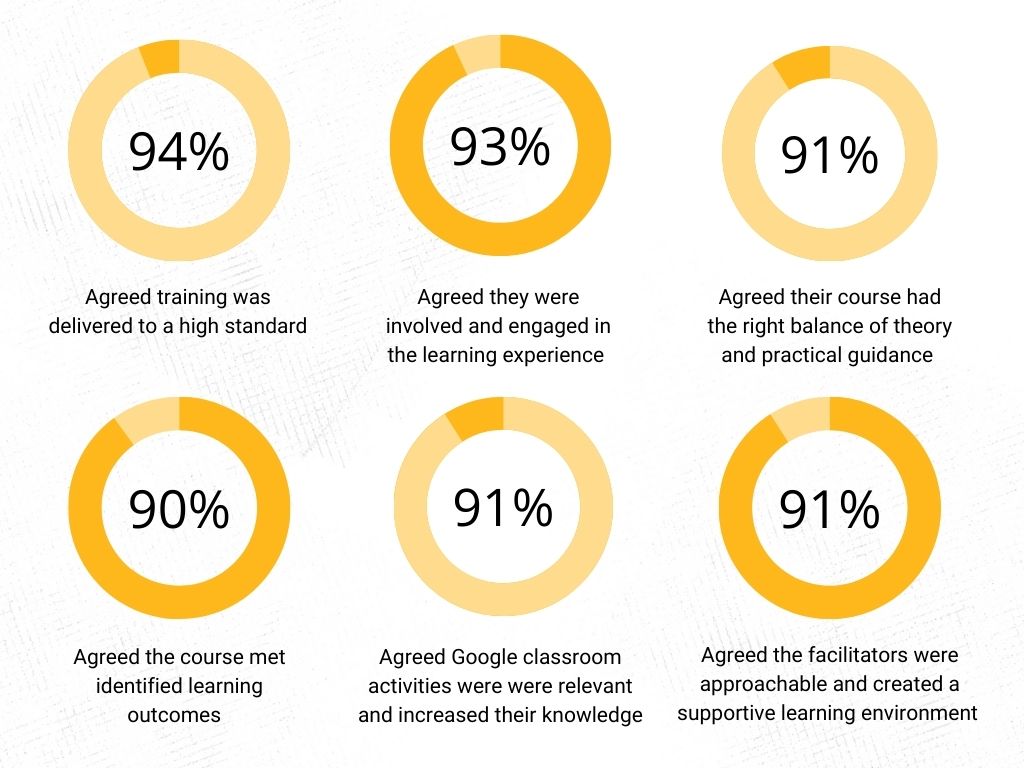

We’ve had a busy year delivering essential training for people to be able to do their jobs across the justice sector. And we’re delighted that feedback shows 94% of people agreed our training was delivered to a high standard.

According to a recent survey, almost three-quarters of our stakeholders or their colleagues have attended training delivered by us. Ratings across all aspects of training were very high and the majority of attendees agreed strongly with each statement. Trainers were particularly highly praised.

We’re really pleased that we’ve been able to make a difference – helping our colleagues in the justice sector develop and widen skills for their day-to-day work. And this will have a positive impact on the individuals they’re working with who are in touch with the justice system.

We have nine colleagues across our learning, development, innovation and Caledonian team who deliver training right across Scotland. The range of expertise in the training team is one of our greatest assets. Across the whole team we have people with backgrounds in teaching, social work, police, intelligence analysis, prison work, counselling, youth work and NHS statistics. Qualifications include postgraduate diplomas in social work and education. When we sit down together to design training we’re bringing a whole array of skills, experiences and knowledge to the table.

And we’ve had some very positive feedback. One person said: “I could not improve it. The course went over and above my expectations.”

More than 1,500 course places were filled in 2022-23 covering all 32 local authority areas across Scotland. Attendees have included justice social workers, people involved in the delivery of unpaid work and restorative justice practitioners. We ran 241 days of live training sessions in person or on Teams and 191 days of training via self-paced working.

In-person training has proved really helpful with one person explaining: “It gave everyone the opportunity to practice group work skills in a safe space.”

But there was also praise for online training. “I really enjoyed the training — very useful to my practice, and engaging throughout. Maybe the best virtual training I’ve been on,” said one attendee.

Getting the balance right between online and face-to-face learning is so important to us. The people we train are incredibly busy and they can’t always drop everything to attend a training day. That’s why it’s so good to know that our online training hits the spot.

Training gave justice professionals a boost. “I now feel a lot more confident in my skills and abilities,” said one. We deliver training on a range of skills to help professionals best support people in the justice system. That includes risk assessment tools, specific practice and group work skills, report writing, restorative justice, Caledonian system domestic abuse work and skills needed for professionals who are supporting those carrying out community sentences.

Our work helps people address the specific needs of individuals who have broken the law to help reduce reoffending and make Scotland safer. Some courses are mandatory – for instance justice social workers wouldn’t be able to do their jobs without the skills taught in our training. We’ve introduced new courses due to demand and now train people involved in the delivery of unpaid work – for those working with people who are carrying out community payback orders. Our team developed a five-day course for those involved in supporting people carrying out unpaid work, which has been approved by Social Work Scotland. This was launched in July and acknowledges the important work being done in the community to support people to complete their sentences.

One person who took part said: “The workers were very professional in the delivery of the training. I find workers very flexible and accommodating and I have an excellent working relationship with the training team.”

New training has also been introduced for restorative justice practitioners and there’s also training in throughcare assessment for release on licence which is for social workers dealing with individuals being considered for parole.

We also deliver training in LS/CMI (level of service/ case management inventory) which is the keystone in risk and needs assessment used to better understand what’s going on for a person who’s broken the law. LS/CMI draws on a vast international evidence base so we know it works well but better still, it’s been adapted for practice in Scotland. The Risk Management Authority worked to make the LS/CMI system even more useful to our sheriffs, social workers and everyone involved in supporting someone to get the most out of their sentence.

A community payback order with supervision for example is based on a really detailed LS/CMI. It helps social workers to focus on the right things when they’re working with people serving their sentence and reduces the likelihood of reoffending by targeting areas like employment, education, relationships and drug/alcohol use. Justice social workers need to complete their LS/CMI training with us so we meet professionals at all stages of their careers: some who are newly qualified, fresh out of university and others who may have been in the field for years but are just moving into a justice role.

Feedback for LS/CMI shows 99% agreed training was delivered to a high standard and provided a high quality learning experience. There has been so much praise for our trainers. “I really enjoyed the course and felt the trainer’s positive and upbeat attitude kept everyone motivated,” reported one person.

Training has helped people with their work. One said: “The course reflected my work context perfectly.”

And the training has left its mark. One person said: “Massive impact, it will shape me into a more mindful practitioner.”

Key statistics at a glance from 2022/23:

Why we need to bring together trauma-informed and restorative justice principles to improve people’s experience of the justice system

Community Justice Scotland’s restorative justice project lead Rachael Moss explains why a move to blend these approaches should be explored to provide more safe and appropriate services.

Individuals’ negative experiences of justice are well-documented and have included reports of people feeling re-traumatised, having no voice and let down by the process.[1]

Court has even been referred to as a ‘theatre of shame’ in one report, forcing people harmed to re-live their experience of abuse, with some survivors enduring accidental meetings with the accused in court.

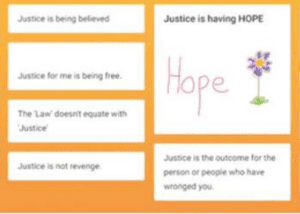

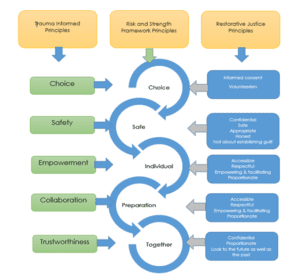

When we ask survivors what justice means, research shows that being believed contributes to their perceptions that justice has been achieved, irrespective of the outcome of any criminal proceedings.[2] In addition, see Figure 1. [3]

Figure 1. Justice is personal to the individual

Does this not make you think about the term ‘justice’ and what that actually means to people who experience harm? Also, how organisations could strive to work together to develop safe and robust mechanisms for individuals to choose how to address harm and its lasting impact by designing a justice process they define and not continuing with what the system prescribes? This doesn’t take away the need for a justice system – it’s about looking at improving it through more trauma-informed, person-centred action.

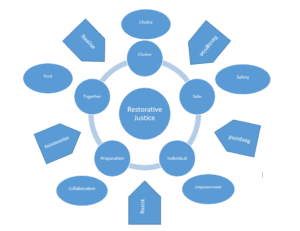

Restorative Justice (RJ) is a process of supported contact between a person harmed and a person responsible for causing harm. RJ takes on various formats, from direct contact such as face-to-face meetings, indirect contact, for example letter writing, or restorative approaches. These can include resolving conflict in educational settings or addressing secondary victimisation from systems.

RJ offers the potential for individuals to achieve a number of benefits already backed up by research evidence.

Persons harmed can experience:

- less fear of re-victimisation

- reduced feelings of revenge

- fewer symptoms of post-traumatic stress

- increased levels of satisfaction, when comparing their experience to the traditional justice process.

—

Scottish Government strategies and visions (e.g. Vision for Justice in Scotland (2022), NHS Education for Scotland – Vision for Trauma Informed Practice, Public Health Scotland: Strategic Plan (2020-23))have similar aims – to promote well-being, recovery and safety, reduce re-traumatisation and further harm across communities. So how can RJ support these aims?

This article admittedly presents more questions than answers, but I think that’s a good thing, as it offers a platform for exploration, innovation and collaboration on an agenda I think we all agree on – how the justice system and those who work in it can become more trauma-informed and responsive to all individuals in Scotland?

Being trauma-informed is about understanding how trauma exposure affects a person’s neurological, biological, psychological and social development.

Recent research on risk and mitigation strategies used by RJ facilitators in the UK and abroad, has provided the following recommendations for policy and practice to keep people safe: [4]

- RJ should be based on the assessment of individual people and cases, as opposed to types of people, offence or case

- Risk assessment and mitigation should focus on the RJ process and the unique needs of individual people

- Risk assessment of serious harm and reoffending is the duty of criminal justice agencies (e.g. social work or police)

- Multi-agency working is key to an RJ process, but it should be led by the person harmed and managed by the facilitators

- The preparation stage of an RJ process is a key measure in identifying and mitigating risk. The more sensitive and complex a case, the more time should be allocated to pre-meetings

- High quality training and experience are required for the facilitation of sensitive and complex cases and co-facilitation is recommended

See mitigation and risk in restorative justice for more detail.

RJ and trauma-informed principles have many complimentary factors and the risk and mitigation research paper helped guide my thinking into the exploration of a trauma-informed RJ risk and strengths framework.

By fusing together trauma informed and restorative justice principles I’ve come up with ways to support the development of a risk and strengths framework. This will hopefully strengthen our ability to provide safe and appropriate services that people can access, that reduce re-victimisation and support recovery.

I include the ‘5 Rs’ of trauma-informed practice into RJ development and delivery in Scotland. These are: Realising how common the experience of trauma and adversity is, Recognising the different ways that trauma can affect people, Responding by taking account of the ways that people can be affected by trauma to support recovery, opportunities to Resist re-traumatisation and offer a greater sense of choice, control, and empowerment, recognising the central importance of Relationships. See Figure 3. and how this could contribute to the development of:

- a risk and strengths framework for RJ

- safe and legal information sharing for RJ

- high quality training in RJ in collaboration with experts with lived and professional experience

I offer these tools as a starting point for collaboration, so we can begin to explore how we continue to reduce some of the negative impacts people who’ve been exposed to trauma experience when they access the justice system.

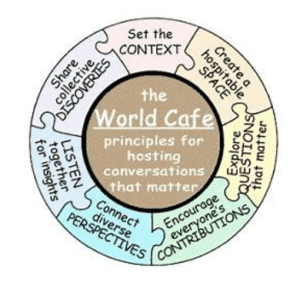

Early this year I will lead a research project to complete a series of ‘world cafés’ with experts with lived and professional experience, to develop a trauma-informed risk and strengths framework for RJ.

‘World café is a restorative approach used to facilitate group conversations where everyone is valued, included, respected and given a voice. Moving away from traditional focus groups, this method creates a safe environment that mimics a café. I look forward to hosting these in the new year and welcome anyone to get in touch who wants to have a conversation.

Figure 2. World Café Guidelines

Figure 3. Fusion of trauma informed and restorative justice principles

[1] Thomson, L., (2017). Review of Victim Care in the Justice Sector in Scotland. The Crown Office and Procreator Fiscal Service Review of Victim Care in the Justice Sector in Scotland.pdf (copfs.gov.uk)

[2] Brooks-Hay et al (2019) Justice Journeys: Informing Policy and Practice Through Lived Experience of Victim-Survivors of Rape and Serious Sexual Assault

[4] Shapland et al (2022) risk and mitigation for restorative justice

How communities can play an important role in helping people in addiction recovery

David Best, a Professor in Addiction Recovery at Leeds Trinity University’s Faculty of Social and Health Sciences, explains the science behind recovery

It’s generally recognised that addiction is a chronic and relapsing condition. But in recent years it has become apparent that the majority of people with a lifelong substance addiction – even to drugs like heroin and cocaine – will eventually achieve a stable and drug-free recovery. This results in a better quality of life, active participation in their communities and some form of ‘giving back’ to repair the harms they have done.

We now have a science for how that happens, based on a concept known as ‘recovery capital’. This refers to the strengths and breadth of internal and external resources a person can call upon to support their recovery journey. For the last 10 years my work has been around how to make measuring recovery capital more accurate and effective and how it can be presented in a form that is engaging, acceptable and meaningful to people on their own recovery journeys.

This has culminated in my development of an evidence-based assessment and recovery planning tool I’ve called REC-CAP (first published in 2017). This is used to assess an individual’s recovery strengths, barriers and unmet service needs. It supports trained navigators to guide people in carrying out recovery goals and measures success achieved. It has now been completed by around 20,000 people in the UK, United States, Canada and New Zealand.

Most people who have completed the REC-CAP are based in recovery residences in the United States – which offer specialised support for people dealing with addictions. Indeed, it is not possible for organisations in the state of Virginia who provide recovery housing to get state funding for this if they do not use the REC-CAP and this is likely to happen in Michigan in the near future as well.

This work has allowed us to test who does well and who is at greater risk of drop-out and relapse, which could result in reoffending and returning to prison. In the UK, we are hoping to start a pilot run of the REC-CAP in a number of adult male prisons, but there are some big lessons from the US that we could learn here. We need a commitment to evidence-based practice and a government commitment to both recovery research and applying that research to everyday practice.

The work in the United States also operates on the understanding that recovery is a process in which a safe place to live is essential and that a recovery model requires a commitment to sober living facilities for people early in their recovery journeys.

More generally, the lesson from our work in the US is about moving away from a clinical environment which focuses on someone’s struggles towards an approach concentrating on their strengths where peers are of central importance. There is a recognition that recovery happens in communities, not in specialist clinics.

I have been very fortunate to be able to champion this work across seven states in the US and I was recently presented with a Recovery Innovations award by the National Association of Recovery Residences at its annual conference in Richmond, Virginia. Not only that, but several housing providers offered personal testimonies about how the REC-CAP and the broader model of strengths-based working had transformed their working lives.

The US will remain at the forefront of innovation and science in this area but the publication of a new drug strategy (“From Harm to Hope”) offers a meaningful opportunity for real change which I hope can be adopted further afield. Innovative practice must be matched by a commitment to recovery science and looking at new ways of addressing the complex and growing challenges faced by families and communities supporting people through addiction recovery.

Restorative Justice: What’s next for Scotland?

Community Justice Scotland’s Head of Restorative Justice Gemma Fraser looks to the future of the service

When I am asked what is next for restorative justice in Scotland I turn to my team work plan and the challenges we still face.

These are around restorative justice – or RJ – being more widely accepted and in securing the necessary resource for this trauma-responsive approach to obtaining meaningful justice for those harmed by crime and offending. I sometimes forget to reflect on how far we have come, and the fact we continue to take big steps down a path forged over decades by passionate, driven and creative RJ experts both in Scotland and internationally.

While the current economic and social challenges are real, we must remember that while innovation and transformation may seem difficult in the face of wicked problems, without them we are doomed to simply recover broken systems and fix things in the short term without eyes (and hearts) on longer-term gains. As I was reminded recently, ‘Two things can be right at the same time’.

We must save our justice system and the people within it, but we must also renew and transform justice for those who experience it.

With that in mind, we will now seek to better embed RJ within the core workstreams of the vision for justice strategy in Scotland as a ‘person-centred and trauma-informed’ approach. In the first half of 2023 this will mean a policy and practice framework to underpin RJ as a parallel process to our criminal and community justice systems. This will be collaborative to answer questions on how, when and where RJ can be accessed. It will also ensure the voices of those affected by harm are present and reflected in policies as well as the design and implementation of Sheriffdom-based RJ services. To further support this, Community Justice Scotland will undertake a research project to assess how RJ services can best meet the needs of those who experience harm with a view to tailoring the requirements to services provided.

We continue to work within the Lothian and Borders Sheriffdom area to understand from stakeholders how referrals could be made to a restorative justice service both from individuals themselves and from professionals. We have also established an expert sub-group to develop a trauma-informed risk and strengths framework in 2023. This will ensure we can work safely with people who wish to explore RJ and consider the right information from them and the services who support them towards best achieving their desired outcomes.

Other plans include expanding our engagement across services, partnerships and sectors to support improved understanding of RJ, and to demonstrate the use of restorative approaches within the criminal and community justice systems. These include healing circles, story-telling and letter-writing. I would also hope to test RJ with people who are already seeking this, in order to ensure the process is effective, collaborative and safe.

We owe it to those who experience harm, and those who have dedicated their lives to RJ practice, empowerment and choice to keep going. So we do and we will. I only hope to make them proud.

Restorative Justice – A Tool for Change

Inesa V?lavi?i?t?, Restorative Justice Administrative Officer, at Community Justice Scotland explains what she’s learned in her role

*Content warning: This blog includes references to family trauma and grief for a child*

—

Everyone held their breath as the mum described the unimaginable sorrow that engulfed her family after her teenage son’s death.

She had come to speak at our school in Lithuania as her son who’d been killed had been a classmate. The mum was joined on the day by our country’s president who had come to offer his condolences to the family and to those of us who had known the 17-year-old boy. We were also given the chance to speak and ask questions.

But I will never forget the emotional intensity I felt as the mum spoke of the impact of her son’s death. She addressed the president in the room and also spoke with a message to the person who caused her son’s death who wasn’t there and explained how the justice process had affected her.

Her words were powerful but weren’t calling for answers. There was no rational reason she could be given for what had happened that could bring her any comfort – but she insisted on being heard.

As I listened to the mum I had so many questions in my head around how it could be possible to rebuild your life in the aftermath of such tragedy and loss. I wondered how someone could live with such immense trauma and pain. I didn’t know back then – that the mum speaking out was a form of restorative justice in action.

And little did I know that 16 years later I would be in Scotland and learning through my work about the ways of addressing harm caused to people and how a safe space can be provided for unearthing much needed answers.

For the past few months I have been supporting the delivery of the initial test project for the restorative justice service development across Scotland. For those who are new to the concept just as I was not so long ago, I would define restorative justice as a voluntary and consent-based process, offering contact between someone who has experienced harm and the person responsible.

The approach involves many forms of communication dependant on what is best for the parties involved. The planned and structured dialogue is delivered by specially trained facilitators and only after a careful and robust risk assessment. But it is a parallel process to the criminal justice system, not a replacement. Restorative justice does not impact a justice outcome in any shape or form.

Although there are plenty of descriptions out there explaining what restorative justice is and what it does, for me its value lies in giving a choice and a voice to survivors, empowering them to decide what they need in order to open the inner path towards self-healing and gaining closure.

It speaks to people’s intrinsic need to be heard and understood, and gives back control to their lives. This subsequently enables them to reconnect with the world and start anew. This process also has evidence-based benefits for those who cause harm. It can help them understand the impact of their actions, leading to less offending. And it can contribute to building social cohesion when they return to their families and communities.

The path to a successful delivery of high quality restorative justice services has many obstacles. There are still some misconceptions about how the service actually operates. Communication around the development of these processes is nuanced and complicated yet essential to aid understanding.

Giants must be battled if we are to change the chain reaction of offending, move forwards positively and constructively in search of a regenerative future in the ever-changing world.

Restorative justice urges us to open our eyes, ears and hearts and carries a hopeful message. I too have hope and trust that armed with knowledge and a more outward-focused approach to the vast terrain of lived experience, we can harness restorative power. With it we can cultivate empathy and build the sustainable, community-minded society we all want to live in. In the words of the famous pioneering scientist Marie Curie: ‘Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less’.

Better support for children and young people dealing with the justice system

The Care Inspectorate’s Head of Professional Standards and practice Henry Mathias explains draft proposals for a ‘bairns’ hoose’ system for Scotland. Plans are underway to improve the way children are treated by the justice system in Scotland.

This will involve introducing a bairns’ hoose system – modelled on the Scandinavian barnahus – of a child-friendly space bringing services together in one place. This will support children and young people through what is currently a complex system and reduce the number of times they have to repeat their story to different professionals.

The aim is to ensure all child victims or witnesses and their families, have all the care, support and services they need delivered under one roof. Introducing barnahus is an exciting opportunity to build on Scotland’s strengths in how we respond to children who have experienced abuse and violence.

The Care Inspectorate is working with Health Improvement Scotland to develop a set of standards for a barnahus (bairns’ hoose) model in Scotland and have developed draft standards and a children’s version for consultation.

Different agencies are working together to improve the quality of investigative interviews and make them less stressful for children taking part. We’re working under the Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC) model which is the national policy framework aimed at supporting the wellbeing of children and young people.

Services are constantly improving the way they respond to allegations of harm. Recent changes include new standards for forensic medical services and greater support for vulnerable witnesses. Introducing barnahus is the next phase of this national reform programme.

Barnahus or bairns’ hoose, originated in Scandinavia and has become commonplace across Europe. It means children can tell the statutory authorities what happened to them in a child-friendly and supportive place.

Introducing barnahus to Scotland should mean that children no longer have to repeat their story to different professionals in different locations. Instead all professionals work together as part of a specialist team in one location – in a building designed for children.

From the outset, therapeutic support should be available for children who have experienced or witnessed abuse and to family members. Bairns’ hoose should mean that fewer children have to give evidence in court which could result in them experiencing further trauma.

The standards would apply to children under the age of 18 in Scotland who have been victims or witnesses to abuse or violence and also children under the age of criminal responsibility whose behaviour has caused significant harm or abuse, to ensure they have access to trauma-informed recovery, support and justice.

At the Care Inspectorate we’re pleased to continue our joint work with Healthcare Improvement Scotland developing integrated standards for health, social care and social work. Agreeing national standards is the first step in the journey for Scotland to establish bairns’ hoose.

We have worked alongside groups of children with lived experience, as well as professional organisations to help draft bairns’ hoose standards. Children with lived experience have directly contributed to the wording of the draft standards and a child friendly version has also been produced.

The public consultation on the bairns’ hoose standards concludes on 4 November 2022 and we’re keen to hear people’s views before then.

Find out more and take part in the consultation by clicking this link.

How the revised National Strategy for Community Justice can lead the way to change lives

The Scottish Government has published a revised National Strategy for Community Justice to build on progress made and provide a roadmap for future improvements. Community Justice Scotland’s specialist advisor Keith Gardner explains why this is an important opportunity for a change for the better

Change shouldn’t just be about doing something differently – it should be about improving the way you do things.

US General James Van Fleet summed it up when he said: “I’m always willing to accept change, just as long as it isn’t change for the sake of change. If that change will result in a better way of doing things, then I’m all for it.”

When it comes to the Scottish justice system it is not difficult to identify the problems, for example, a high prison population (and particularly those on remand awaiting trial), the varying use of community-based sentences, etc. But how do we make the system better for those whose lives are impacted by it?

The vast majority of people affected by the justice system in Scotland are not found in the courts or in the prisons, they are in the community.

Agencies have been involved in ‘community justice’ for many years but it’s only since the Community Justice (Scotland) Act in 2016 that there’s been a legislative duty for this to happen. This led to the setting up of Community Justice Scotland as a national body to reduce reoffending and to play a central role in the continual improvement of Scotland’s justice system.

Key players in local authorities, police, NHS, Scottish Prison Service, Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service and others including vital partners in the third sector come together to plan and deliver coordinated services at a local level. This has been the model for the delivery of community justice since the introduction of the act, encompassing people who have done harm, but also those who have been harmed and all of the people and agencies around them in their communities.

Legislation might lay out the responsibilities for partners and agencies and tell them what they need to do, but it does not tell them how to do it. The desire to change, to improve is one thing, but in order to get to that place, we need a clear idea of where exactly we are going.

The Scottish Government has published a strategy for community justice this year – a required update of the original one which accompanied the 2016 Act. Now we are older and wiser, the strategy reflects where a modern justice system can go and what it can be.

However, a strategy remains a two-dimensional piece of paper until the willing and motivated move in the same direction to hear, listen and act on the experiences of those who have been in, through and around the justice system.

All the moving parts of what we call the justice system need to focus on doing the right thing, for the right reason at the right time. The 2022 strategy is a time to refocus on working together and to do that through a trauma-informed and person-centred lens – creating a system that leaves no-one behind.

There are key aspects of the strategy that bring a re-focus and opportunity to keep people out of the system. One is to optimise the use of diversion from prosecution in creative and meaningful ways to help people exit the system at the soonest juncture in a way that is safe, supported and leaves a minimal justice wake in their lives. This is where the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) is able to refer a case to social work – and their partners – as a means of addressing the underlying causes of alleged offending.

The victim-led process of restorative justice, with multi-agency support, offers an option for those who have been harmed to take control and to aim for, where they so wish, understanding and closure: the emphasis being much more on restoration than justice.

For those who, for whatever reason, progress into the justice system, there’s a strategic commitment to ensure that people get access to high quality services and interventions that are tailored to their specific needs while also having a correct and proportionate focus on the protection of those who are vulnerable in our communities.

In order for this to happen, complementary strategies need to run in harmony, such as youth justice and the Equally Safe strategy around violence against women and girls. Progress will supported through the revamped Outcomes, Performance and Improvement Framework (OPIF), which will help local areas to realise the ambition of the strategy by giving them a tool to drive and support local community justice activity. The OPIF will also help form the basis of the annual overview of the health of community justice across Scotland.

The strategy also recognises the impact of the wider support needed for people – not just when they are in the system. There are also the life-long links of recovery and the practical aspects such as housing, health and employability – all of which need to be in place for people beyond their interaction with the justice system.

This needs the partners, the people and our communities to come together through effective engagement and has to be driven by leaders who are connected, committed and compassionate.

The big question is will this strategy succeed? To answer, I am reminded of motor company magnate Henry Ford who said: “If everyone is moving forward together, then success takes care of itself”.

How problem-solving courts are making a difference

Sheriff Jillian Martin-Brown explains how her specialist court works

I have seen the positive differences Forfar problem-solving court can make to people’s lives. It provides extra support and supervision through a specialist court hearing that can really improve someone’s opportunity of rehabilitation through community sentences.

I am the sheriff who currently presides over the court and I’ve seen how it can support people to complete their community payback orders. These can include unpaid work, supervision, programmes to address alcohol and other issues or all of those requirements.

It began as a partnership between sheriffs sitting in Arbroath Sheriff Court and the Glen Isla project, a women’s community justice service run by Angus Social Work Department. That partnership was transferred to Forfar in 2016.

The court currently deals with summary cases – the less serious ones – where addiction or other issues can make completion of community sentences very challenging.

At the moment we hold a monthly dedicated problem-solving court. In this I aim to use the authority of the court to enhance the potential of rehabilitation through community sentences. My aim is to combine different types of treatment provided in the community with regular court reviews so that I can monitor the progress of the people I sentence.

Glasgow and Edinburgh also have specialist problem-solving courts but Forfar is different in that it covers a wide geographical area that is more rural in nature than the large urban courts. While there are no formal entry criteria, there is a particular focus on women and young men, who are often in need of the most support to complete their community sentences.

Where appropriate, I take a trauma-informed approach to deal with people by recognising the potential impact of adverse childhood experiences, and take into account that some of the behaviours of the people before the court are a result of traumatic experiences.

A practical example is that we schedule the problem-solving court in the afternoon, when the court building is usually quieter and less busy. My experience is that people feel less intimidated discussing their progress within that setting.

Each person’s journey is different, but where appropriate, I will start off by sentencing someone to a structured deferred sentence for a short period to see how well they comply.

This is a structured intervention for a period of time for individuals who have been convicted, before they’re given a final sentence. It can put support in place to help people address a range of complex needs and look at the underlying causes of their offending behaviour. This would usually be followed by a longer period of a structured deferred sentence with a view to eventually imposing a community payback order with regular reviews.

For many people these types of sentences can be longer and more demanding than a short custodial sentence. Relapses can be a part of recovery and regular reviews can pull people back on track and ensure they remain accountable.

I have seen positive outcomes that have been assisted by the reviews in the problem-solving court. For example, one young woman who had been sentenced to two community payback orders was supported by the Glen Isla Project to obtain her own tenancy and start a college course. She was justifiably proud of her progress in changing her offending behaviour and justifiably proud of how hard she worked to achieve that.

Looking to the future, I hope that we will be able to continue with the specialist court and support people with completing these demanding sentences in the community.

The gentle art of nudging – Dame Laura Lee

What everyone can learn from the way Maggie’s treats people and nudges them towards healthier behaviour

Our chief executive Karyn McCluskey recently talked about how we should look at how cancer patients are treated when trying to help people battling addiction: Scotland’s drug-death crisis: How treating addicts as well as cancer patients would make a real difference.

She praised the work of Maggie’s cancer charity and suggested there could be centres like theirs to support and manage addictions.

We hear from Maggie’s chief executive Dame Laura Lee about what we could all take from the holistic approach adopted by their centres:

‘The vision of Maggie Keswick Jencks was for a new way of helping people with cancer. She had an idea for a place that felt warm and welcoming, a place of expert support and information, a place that made each person feel valued as a human being.

Her vision became a reality and now, 25 years after our first cancer support centre opened in Edinburgh, we now have 24 Maggie’s across the UK and a growing international network. We have helped hundreds of thousands of people to live well with cancer. We can’t promise to change the outcome, but we can promise to help give people the best possible chance. To find hope.

And one of the ways we do this is called nudging. A subtle hint, a suggested change, a gentle recommendation.

We have been doing this for 25 years and now politicians and health professionals are beginning to understand that when it comes to getting people to change their behaviour for the sake of the own health, nudging is far more successful than lectures and dictates.

We don’t tell people what to do, we don’t tell them what not to do and we don’t judge them. What we do do is use our expertise to gently guide them towards a healthier way of being.

And then of course support them to make those changes in a way that is manageable and allows the person to feel more in control of their mental and physical health. Our professional staff are experts at this. Some of it is instinct, but a lot comes from truly listening to the people they are supporting.

A person might be talking about feeling unsupported by a partner, but a few throw away comments about being unable to sleep might lead the cancer support expert to nudge towards is a sleep management course. Resentment at finding yourself as a carer, might be best met with a nudge towards healthier eating and gentle exercise. Ways of helping the person feel healthier, more energised and more able to care.

So for 25 years we have been nudging people towards taking small steps to give themselves the best possible chance during treatment, to ensure they have the energy to be carers or to protect against recurrence as best as possible. With that nudging though comes more than just the obvious physical benefits. Nudging rather than dictating allows people to feel empowered and in doing so feel better mentally and emotionally as well. Suggesting options, step by step, offers people choices when it might otherwise feel as if they have none. And while I am not an expert in other fields, I firmly believe what we have learnt in our 25 years of supporting people with cancer, as well as their family and friends, could benefit other people with different health problems.

Ultimately, behind every emotion, struggle and challenge lies fear and when it is all said and done, more than anything Maggie’s helps people cope with fear. We do this by listening, understanding, nudging towards the right support for them and refusing to judge when the slips come.

Who wouldn’t benefit from that?’