11 Books for the Smart Justice Generation

To celebrate the launch of the #SmartJusticeGeneration hub, we’ve teamed up with brilliant book blogger Rebecca Brown AKA That Bloody Woman Reads to curate this (mostly Scottish!) list of suggested reading for those interested in social justice.

The list is deliberately varied; a mixture of fiction, non-fiction, essays, short stories and poetry. Follow Rebecca on Instagram for more brilliant book reviews and suggestions. Happy reading!

Community Justice Scotland is on a mission to make useful resources accessible to anyone who needs them. The #SmartJusticeGeneration hub is a one-stop shop for anyone with an interest in social justice.

1. Happiness is Wasted on Me by Kirkland Ciccone

‘This is a novel about where and how we live and the ways in which we choose and refuse to tell the stories that shape us. Ciccone’s writing asks big questions about whether we can freely create the lives we choose to live. This is a novel that peeks its head around many closed doors but is ultimately a celebration of greater Glasgow and its ugly parts — poverty, violence, dark humour and complicated domestic lives.’

2. On Connection by Kae Tempest

‘Tempest examines the duality of who we actually are and who we would like to be through the ways in which we cope with the moveable parameters of our lives. This is a book about becoming a better reader of and listener to other people in the hope that human connection can happen anywhere. Tempest proves that what connects us is invariably more powerful than what divides.’

3. Slug by Hollie McNish

‘This is a book of multiple forms — a mixture of prose, poetry, short stories and essays — that covers topics such as contemporary motherhood, lockdown, grief, sex and, ultimately, being human. McNish writes about the trails we leave behind and the choices we make as we move forward in a way that will make many of us feel seen. Highly recommended — and it’s filthy drop dead gorgeous.’

4. Mayflies by Andrew O’Hagan

‘This is a novel about the daft and romantic vitality of youth, following a band of bottle-sharing brothers as they take their own particular measures against the struggle to live a complete life. O’Hagan explores dreams of newness, of mourning and memory and the wish to separate from home, from which identity is almost always inextricably linked. A journey to the interior of male fragility, O’Hagan proves that difficult things do not cancel out other difficult things as we get older. The most moving novel I’ve read in a long time.’

5. Duck Feet by Ely Percy

‘This is an episodic novel about growing up in the mid-naughties in Glasgow. Brimming with the pressure of social expectation, Percy offers an important portrayal of the richness of working class lives in fiction told through teenage eyes. Percy’s writing gives the gravity and the silliness of adolescence equal weight as their characters struggle to navigate and invariably lack the agency to resist the influences that govern their lives — the internet, drugs, poverty, body image, peer pressure, grief.’

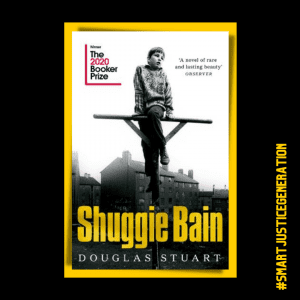

6. Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart

‘This is a novel all about 1980s Glasgow; its furloughed dreams and deep rooted prejudices; about love that’s tested and love that’s conflicted – gone wrong, denied or misunderstood. Stuart offers unapologetic vignettes of compassion, bravery and horrific roaring violence from Glasgow’s insulated and isolating housing schemes as his characters struggle to survive within and invariably lack the agency to fight against the structures of oppression that contain them. Despite the specificity of time and place, this is ultimately a universal story of the resilience of the human spirit and putting on a brave face for the world.’

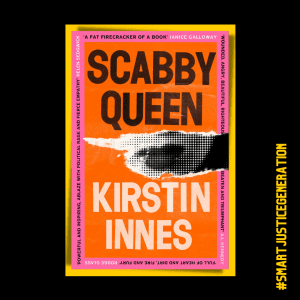

7. Scabby Queen by Kirstin Innes

‘This is a novel about private lives colliding with public image. Like its unapologetically outspoken protagonist, this book does not shy away from big themes – of activism, protest, solidarity, feminism and working class politics – and what they mean in a world of increasingly information-fed madness.’

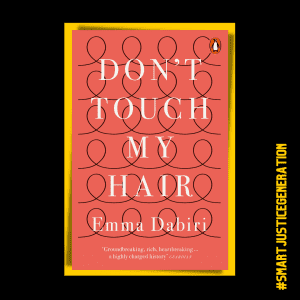

8. Don’t Touch My Hair by Emma Dabiri

‘I was completely fascinated by this book where hair becomes the living embodiment of a complex visual language. Part social history, part memoir, Dabiri shows that the scope of its concerns are also gendered, technological, philosophical and spiritual. Far from being “only” hair, this book proves that the very serious business of black hairstyling culture can be understood as an allegory for black oppression and, ultimately, liberation. Essential reading for everyone.’

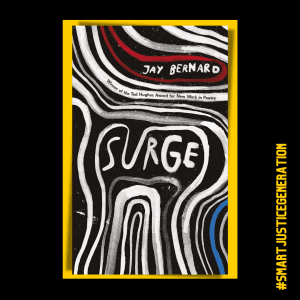

9. Surge by Jay Bernard

‘This is a debut poetry collection that powerfully resonates in our current moment. Bernard brings together public narrative and private inner worlds to create an original exploration of contemporary black British experience. Functioning as a mirror of the present but with an unbearable sense of history repeating, I had to stop reading these (sometimes) difficult poems on multiple occasions.’

10. Let Me Tell You This by Nadine Aisha Jassat

‘This is a stunning poetry debut from one of my favourite Edinburgh-based poets. I heard Nadine tell some of these poems at an event last year and was amazed by the way she doesn’t hold back from questions about racism, dual heritage and gender-based violence.’

11. Hings by Chris McQueer

‘Hilariously uplifting, vibrant and surreal stories about working class Glasgow – this one felt like home. McQueer brings some dangerously relatable stories about Glasgow, my favourite Scottish city.’

Why we need to help everyone understand our justice system – Student blog

To mark the launch of #SmartJusticeGeneration – a FREE online resource for students – Katy Ramage, a third-year law student at Strathclyde University in Glasgow, gives her view on why we need to put people at the heart of the system

‘I applied to study law at university because I have a genuine thirst for knowledge on how ‘stuff’ works. As law essentially covers every part of life, it was a perfect fit for me.

Classes I have taken over the first two years of my degree have helped to explain the inner workings and reasoning behind all kinds of legal disputes. I’ve enjoyed learning about criminal law the most – yet despite in-depth teaching in class and personal reading I still feel as though I have barely scraped the surface of the complexities of the criminal justice system. At this stage I admit I’m filled with panic at the prospect of confidently supporting a client as I don’t yet fully understand the inner workings of the system. So I can’t imagine how frightening it must be for someone with no knowledge of the law to be on the other side of the system and be charged with a crime.

As every crime and the parties involved are all unique, it’s no surprise that the justice system mirrors this individuality.

However, if someone like me who’s studied law for two years finds the process difficult to follow, I can’t see how someone with no experience could cope. To me this is a glaring problem.

The complex justice path probably resembles a labyrinth, sometimes hard to navigate for those without a background in law. The knock-on effect for anyone facing this would probably be a loss of interest in the proceedings – and who could blame them. If you don’t understand the process, how can you be expected to engage in it?

We need to treat people as individuals and help them understand what’s happening. I want to go on to become a solicitor so I’m concerned that future clients would see it as a scary, daunting experience if they don’t understand the system. I hope this changes by the time I’m practising law.

That’s why I am particularly impressed by Community Justice Scotland’s digital map which navigates through each stage of the criminal justice process. For anyone involved with criminal justice this is an invaluable tool for understanding and breaking down the complexities of it. Not only does it explore every path available – so those accessing the system can see where their case fits on the wider scale – but it also explains what the steps mean in a simple way. I think it will help lead to a greater understanding of the criminal justice system.

Hopefully understanding allows those accused of a crime to see a way out, rather than being stuck in a cycle of reoffending. If they are aware of each stage and why each stage is necessary, it could help them become more engaged and I think it would also aid rehabilitation.

It’s only one resource but it shows a promising step in the right direction for the future of the criminal justice system.

Transparency and individuality are definitely two of the key aspects that a future system should prioritise.

Alongside this, helping rehabilitate offenders is important. Community sentences provide a different option and have been shown to be more effective at preventing reoffending than short prison sentences. People released from a short custodial sentence of 12 months or less are reconvicted nearly twice as often as those sentenced to serve a Community Payback Order (CPO). Allowing different methods of dealing with crime is very forward thinking and puts the people involved at the heart of the system instead of the procedure.

Creating a more visible process for the criminal justice system is needed to allow for proper engagement from those involved. Initiatives such as the navigating map for the justice system from Community Justice Scotland are ones that should definitely be built upon to allow for an even greater understanding. These projects allow for hope that a smarter justice system is an achievable goal for the future.’

Check out the #SmartJusticeGeneration Hub today!

5 things Netflix doesn’t teach you about criminal justice

Community Justice Scotland’s Digital Marketing Officer Tash Pile reflects on the ways in which depictions of criminal justice on TV can often be misleading.

Barely a week goes by when there isn’t a new true crime documentary trending on Netflix. Making a Murderer; I Am a Killer; The Devil Next Door… the list goes on.

Yet many of us barely give the justice system a passing thought. It’s fair enough really, if you haven’t come into contact with it, why would you?

That was the position I was in before I joined the Community Justice Scotland team last year. Eight months in, I’ve taken some time to reflect.

Here are the top five things I’ve learnt:

1. On Netflix and in the media the depictions of criminal justice and the people who commit crime are made to fit easy-to-digest binaries. It comes down to good versus evil; criminal or member of society; guilty or not guilty. We settle-in with a glass of wine to watch the latest true crime documentary, steeling ourselves to be shocked and entertained. But the crimes shown on Netflix are often extreme, rare and complex examples.

2. “Lock ’em up and throw away the key!” This is an unhelpful mentality and is unlikely to lead to a safer society. Prison actually costs us more as taxpayers than the alternatives (not to mention the physical and emotional disconnection with the outside world that it creates). A Community Payback Order gives the person an opportunity to learn from their mistakes and give back to the community that they have harmed. Statistics show that those with custodial sentences often enter into a cycle of offending as they are not given the chance to learn how to contribute to ‘regular’ society.

3. This leads me to the language we use to talk about criminal justice. We simply don’t have the vocabulary to talk about crime compassionately. Our media outlets can be unhelpful – headlines slashed across newspapers and online: “MONSTER BEHIND BARS!” and “PURE EVIL?” offer no chance to reflect and no impetus to find out more about the person behind the crime. Often (though of course, not always) the person’s life leading up to them committing a crime is just as tragic as the crime itself.

4. Describing the trauma that a person has been through is not “making excuses” for the crime they have committed and is always relevant to mention. As a civilised society we pride ourselves on being compassionate to others who have been through adverse experiences. Why then do we judge the parent who has turned to shoplifting to feed their children but have endless compassion for those who would lose out under government plans to stop funding school meals?

When and how does compassion turn to outrage – and is that helpful?

5. The criminal justice systems in the US and UK are very different. Court process; jury selection; sentencing and much more, work differently. It is important to note these differences if we are to begin to understand what is happening to people who commit crime closer to home and ultimately, to decide if our justice system is fit for purpose in our own society.

We admit that our views about criminals and the criminal justice system are in large part formed by the TV shows we watch and the media we consume.

But in a world that is challenging its binaries and preconceptions in other areas, isn’t it about time we did the same with depiction of crimes and people who commit them?

We need to admit what we don’t know and open ourselves up to learn, if we want to be a part of creating a fairer, safer Scotland.

Complex processes to bitesize chunks: How to use the CJS digital justice map

Community Justice Scotland’s new projects officer Victoria Guthrie shares her positive experiences of using the digital resource.

I have worked in or around the justice system since 2011 as a researcher and lecturer and perhaps the most striking thing I have learnt, is that it is a complex and somewhat confusing landscape. There are so many interconnected parts so it can be really challenging to get your head around it. That is one of the reasons why I love the interactive digital map produced by Community Justice Scotland. It breaks down the different components into bite size chunks and connects some of the dots for you.

Coming from an academic background, I have spent a considerable amount of time learning and teaching other students about Scotland’s justice system. Many of the students I have taught over the years have not been justice experts but instead psychology, nursing, or public health students who are trying to grapple with the complexity of the system, trying to understand the intricacies of it and discovering how their expertise might fit into it. I have used the digital map in many a lecture to highlight this too them.

Often when I’ve used the digital map I’ve worked through each section with students. We’ve looked at what constitutes crime, we’ve debated moral, philosophical, and legal underpinnings.

We have thought about all the factors which lead to justice involvement, the factors which influence trajectories through the justice system and the factors which support people out of it. As a social justice geek, I do this with friends and family too in a bid to highlight the impacts of cumulative disadvantage and adversity but also to highlight the importance of being kind, empathetic and supportive to each and every person you encounter. I think the digital map really helps these conversations.

I’ve recently joined Community Justice Scotland as a projects officer, providing research and analytical support and contributing to project management processes. One of the reasons I wanted to work for the organisation so much is that they believe in people and they believe that a more socially just Scotland is possible and are striving to make that a reality. I’m passionate about improving outcomes for people in or affected by the criminal justice system. I have a particular interest in interventions which support mental health and substance misuse recovery as well as parenting and family support programs.

It’s not just students who can benefit from this map. Many individuals working in the system and many of the people directly affected by it have talked to me about difficulties they have had trying to navigate their way through the Scottish justice system. The digital map can help them too. Coming into the justice system can be a daunting time for individuals, their friends, and their families. Not knowing how the system works or who/where they can turn to for support can add to the already distressing and anxious time. Lots of people I have met across my time in justice have also commented on difficulties they have experienced breaking the cycle of disadvantage and breaking the cycle of justice involvement. This is why I am particularly excited that the stories of real life people will be added to the digital map and will showcase some of the highs and lows of what it is like to work in or be in Scotland’s justice system.

Restorative Justice: repairing harm in Scotland

Restorative Justice officer Rachael Moss explains how she wants to get people talking about the process that’s helping people heal from harm.

I’m keen to raise awareness and understanding about Restorative Justice across Scotland and how it could help people recover from the harms of crime.

Restorative Justice (RJ) is a process that offers safe and structured communication between people who have been harmed and people responsible for causing harm.

It’s managed by trained facilitators with the overall aim of attempting to address the impact of the harm to offer healing and closure.

Evidence shows that Restorative Justice can reduce the likelihood of further offending, help people recover from the harm of crime, and provide greater satisfaction with the justice process.

My role at Community Justice Scotland is to support and monitor the delivery of the Scottish Government’s Restorative Justice action plan. (Restorative justice: action plan – gov.scot (www.gov.scot) I do this in partnership with the Children and Young People’s Centre for Justice (CYCJ) to ensure consistency across adult and youth services. The three main outcomes of the plan are to make RJ available across Scotland, for it to be delivered by trained facilitators and for there to be an awareness and understanding of RJ across Scotland.

I felt a media clip would be useful to raise awareness and understanding of RJ – but I discovered there weren’t any online which described RJ in a Scottish context.

In Scotland we use the terms ‘person harmed’ and the ‘person who caused harm’. The majority of animation clips I found online used the terms ‘victim’ and ‘perpetrator’ which I feel can be labelling and dehumanising.

Pamela Morrison from CYCJ and myself set out to produce a short animation clip that would illustrate RJ in a Scottish context and raise awareness and understanding among stakeholders, services and the general public. It was important to us that we chose an animator able to produce detailed illustrations as we felt this would be key to grabbing attention and maintaining engagement.

The most challenging part of creating the animation was writing the script and trying to consolidate a comprehensive topic into a short clip. We took on feedback from members of the RJ stakeholder group to ensure key information was included.

We wanted to show the benefits of RJ from people who have experienced it, including those harmed and those who caused harm. We worked closely with Why me? and Youth Just Us who kindly provided case testimonials to demonstrate that RJ offers a different form of ‘justice’ that allows opportunities to have unanswered questions addressed and provide closure.

It was essential that the animation picked up on some of the key principles of RJ. It’s a voluntary process, which requires the consent of both parties and evidence that the person responsible for causing harm accepts responsibility. RJ processes can be terminated by either party, at any point. It was also important to emphasise that RJ is a process that involves careful planning, preparation and risk assessment.

As well as the publication of the animation, we created a survey to measure RJ awareness and some questions to establish the impact of the media clip, which will be published in the summer (2021).

We hope that this animation is successful in getting people talking and raising awareness and understanding among the public, services and institutions. The animation clip can also be used in consultations and training sessions to ensure a basic understanding of the concept of RJ. We hope people will share it far and wide.

There is also a short survey for children and young people aged up to 25 asking their views about RJ on behalf of the Scottish Government. Details here: http://www.cycj.org.uk/news/children-and-young-people-take-our-restorative-justice-survey/ (closes 25 July 2021)

* Please see the following website for on-going updates on the development of RJ in Scotland https://www.gov.scot/groups/restorative-justice-stakeholder-group/

A call for people, not processes at the heart of our justice system

Julia Clarke, former Research Officer, Community Justice Scotland

“However well you know the system, it can still work against you.”

These were the words of a professional I met last year, who had recently found herself in the shoes of the clients she worked with day in, day out. Events in her personal life had snowballed, and she was accused of a crime which she knew she hadn’t committed. And, despite over a decade’s experience of working within the justice system – alongside police, social work and the courts – she found herself powerless, and lost. Why did this happen, and how could things have been different? These are questions I wanted to explore in Community Justice Scotland’s research paper: “Rules for Them and Rules for Us”.

Last year, I set about documenting people’s experiences of Scotland’s justice system to shed light on the complexities of the justice process. Only by sharing research and knowledge can we make meaningful improvements for everyone affected by justice: victims, those accused, and communities across Scotland.

I found that people were often motivated to make positive changes to their lives, if services invested the time, support and resources required to address their individual needs – which often lay at the root of their offending. This person-centred approach encouraged individuals to actively engage in the processes to which they were subject.

“The best thing is that [they] are available and willing to help. I know the ball’s in your court and you need to do it yourself, but you’ve got support [to] keep things on track”. The future could look bright when options, processes and the available support were clearly communicated.

Sadly, this was not always the case among those I spoke with. Many accounts were marked by the experience of disempowerment through process. People commonly described their interactions with the justice system as a series of events that had ‘happened’ to them, rather than something they had actively engaged in. One individual in prison remarked, “It’s rules for them and it’s rules for us… It’s always been two systems”.

The binary notion of ‘them and us’ sparked confusion, frustration and hopelessness among so many. The woman described at the start of my blog was found not guilty, and has built a happy and healthy future for herself. But she remarked in retrospect, “when you are the person accused, that flip of power, that flip of knowledge, that flip of understanding, that engulf of fear consumes you.” If someone does not understand the process they are going through, how can we expect positive outcomes – or meaningful payback – from the people navigating our justice system?

Whether you are a professional delivering our vital support services, or a member of the public reading the latest Courts and Crime section in your local newspaper, it’s crucial we remember it is people – brothers, sisters, parents, young people – who are at the heart of our justice system.

So I ask you, the reader – let us consider how we can better support individuals to take ownership of their journey and view themselves as participants, rather than mere subjects, of the justice system.

“…You’d rather sit down and speak to somebody about what actually happened, and maybe it’ll take a couple of weeks, couple of months I don’t know. Then it’s coming to the conclusion that what you were doing was wrong. And you go away and you’ll no do it again, ‘cause you know in your head, it’s already drilled… You’ve already learned… It’s understanding basically.”

A week from Karyn McCluskey’s diary

There’s nothing typical about a working week in the life of our chief executive Karyn McCluskey. Many think she works exclusively under the justice remit – but her role is much wider. Here Karyn shares her diary from a recent week before the tightened lockdown restrictions came into force.

Sunday

I run 5km for the Moira Fund. It’s in memory of Moira Jones who was killed in Queens Park, Glasgow in 2008. I’ve known Moira’s parents for many years and am in awe of what they have done in their daughter’s name to help others so traumatically bereaved.

Monday

I visit the Governor of HMP Edinburgh. It’s a stain on Scotland that we have so many people in prison when he and an army of others are committed to prevention. So many of those coming in through his doors have mental health problems and trauma hidden by illegal drug use.

During the pandemic I see many who are locked up for long periods, but also the humanity and the humour. It’s strange in this environment to see women tending chickens in a hen house.

So many I meet have known violence, neglect and addiction, have experienced the care system and poverty. There are also those who present a real threat. We must reduce the numbers of those whose offending can be dealt with by other services and leave prison for those who would do us great harm.

Tuesday

I’m on the board of Simon Community Scotland, which works to combat the causes and effects of homelessness and I spend part of the day at a new hub in Glasgow for those who are sleeping rough.

I meet friends there, who are oral surgeons from Glasgow Dental School who are setting up a specialist service for people who are homeless. Drugs, neglect, abuse and violence mean that many end up with terrible problems with their teeth. I think about the particular torture that is dental pain, and the judgements that we all make when we see someone with rotten, missing or broken teeth.

Wednesday

I meet activist Peter Krykant in a café. In recovery himself, he’s campaigning to change the law to allow a safer place for people to take drugs to save lives.

We speak about having both seen the work of drug consumption rooms in Denmark and the challenges faced by those trying to change their lives. There is a huge, incredibly supportive recovery community in Scotland and we are lucky to have them but they need more than luck.

Thursday

I chat with Julie. We originally met through Twitter when she shared her experience of the care system. Whip smart, she lived with me when she started her new job as a trainee solicitor. She is full of imposter syndrome and I sternly try to remind her how good she is.

I also speak to Fiona Duncan who’s chair of The Promise, the organisation charged with making sure the conclusions of the Independent Care Review are implemented. It’s an overwhelming and overdue bit of work. Julie, and too many others, who experienced the care system should have had better lives.

Friday

I have my regular virtual meeting to look at practical solutions now that the justice system is starting up again following lockdown. The problems are complex, and the impact on victims and those who are accused is huge.

I’m working with people from all areas including the prison service, local authorities, third sector and the Scottish Government. We try to chip away at the problems but often without getting to the heart of the solutions. We have to focus on the short term right now – but know that real change will only happen when we address the age-old problems of inequality and injustice . I remind myself every day that I believe we can.

- Some details have been changed.

How vital domestic abuse work has continued during the pandemic (2/2)

In the second part of our #TalkingJustice blog series on the Caledonian System, national trainer and advisor Gill McKinna explains how the team has adapted to the pandemic

Working with men who abuse their partners is fundamental in keeping women and children safe.

Restrictions around the pandemic have made intervention work especially challenging in this area – but it’s been vital that this important work continues.

During this time we have had to pay special consideration to the safety and wellbeing of women, children, men and workers involved in this area whether the work has been continuing face to face or over the phone.

The Central Caledonian team in Community Justice Scotland train staff in local authorities to deliver the Caledonian System. It’s an integrated response to domestic abuse working to assist men to change their abusive behaviour while also offering separate support to women and children.

Usually all of our training is delivered face-to-face however as a result of the restrictions, we have had to adapt what we do. We have been able to continue offering training to staff via online training days and support sessions, with some face-to-face training continuing in small numbers.

We have also published numerous documents offering guidance and support to workers within the system on how to continue delivering the work in a safe manner whilst managing restrictions imposed as a result of the pandemic. The guidance and training sessions have also had a focus on worker safety and wellbeing during the pandemic.

Men who have been convicted of domestic abuse offences are referred to the programme either as part of a supervision requirement on a Community Payback Order or Licence conditions when released from custody. In certain areas of the country men can also self-refer to the programme without going through the court process.

But in most cases men join the programme after they’ve been through the Court process.

There have been delays in the court system due to the pandemic so we’re expecting there will be a spike in numbers being referred to the programme over the next few months.

We take a gendered approach to practice and work with men who are abusive to female partners in heterosexual relationships.

The programme helps men understand any attitudes and beliefs they have developed that prevent or get in the way of them being safe and caring partners.

In the men’s programme there are three components – individual sessions, group work and maintenance sessions. We have also been successful in recently getting a 1:1 version of the programme accredited by The Scottish Advisory Panel on Offender Rehabilitation (SAPOR). This means that if groups are unable to meet, the work can continue on an individual basis whilst restrictions are in place.

It’s vital this work continues to help keep women and their children safe and to improve the wellbeing of women, children and men. Helping men to change their abusive behaviour is key to making this happen.

However this work would not be possible without the committed workers that we have within the system and it is important that we also ensure that we keep the professionals who are working in this area safe and focus on their wellbeing too.

—

Our Talking Justice blog series brings together reflections from across our society. We are committed to changing the conversation about justice, increasing understanding and support for what will make Scotland better for all of us. To that end, we have have created a resource that maps out the Scottish justice system. This has been developed into an interactive digital tool: Navigating Scotland’s Justice System.

Domestic abuse work is helping men change and making women safer (1/2)

As part of the Talking Justice blog series Caledonian National Coordinator Rory Macrae talks about the work of the internationally-recognised system helping change abusive behaviour

We believe that men who abuse women partners have the ability to change and we get immense satisfaction when this happens. But even if they’re not ready to make changes, our work can still help make women safer.

I started working with perpetrators 30 years ago and was involved with designing and implementing the Caledonian System around 10 years ago. It’s an integrated response to domestic abuse working to change men’s behaviour but also offering separate support to women and children.

Men who have committed domestic abuse are referred to the programme either as part of a Community Payback Order or as a supervision requirement when released from prison.

The work is based on evidence and the practice manuals were scrutinised by a very robust accreditation process. I am proud that it is now internationally recognised as a gold standard model.

Research has shown that men who have completed the programme are judged to be lower risk to partners and children. And women who have taken up the service have reported that it made them feel safer.

It is implemented in 19 out of 32 local authorities across Scotland covering 75 per cent of the population and we hope it will eventually be available to all local authorities across the whole of the country.

There are three of us in the Caledonian central team and earlier this year we joined Community Justice Scotland.

Although we’ve previously worked directly with men who have abused partners, the bulk of our work now involves support, oversight and training staff in local authorities to carry out this work.

People tend to think of the Caledonian as a men’s behaviour change programme, and although it’s the man who comes through the door first it’s important to stress the women’s and children’s services are just as important.

Even if a man’s behaviour doesn’t change we believe his partner’s safety can be increased if he’s involved in the programme and she has access to the women’s service.

Some men we work with will not be ready to make changes. But working with a man means we can learn more about the risk he represents. This helps the risk management process and his partner is supported and where necessary given advocacy help. She will be empowered by that involvement to make her own choices and to keep herself as safe as she can even if the man doesn’t change.

It’s a gendered approach and deals only with men who are abusive to female partners in heterosexual relationships.

Clearly women can be violent too – but the reasons for the violence may be very different and the proportion going through the courts is very small.

Our society has traditionally organised itself in a way that gives a disproportionate amount of power to men – even if individual men we work with may sometimes feel powerless.

The attitudes we’re brought up with as men and women impact the way we behave.

We help men understand why they have ended up hurting the women they love. We invite them to think about their behaviour in terms of the expectations they have of their partner and children and also the expectations they feel are placed on them as men.

In our experience perpetrators are very often unhappy on some level with what they’re doing even if they are consciously using abuse to exert control over their partners. We invite men to consider whether in behaving abusively they are being the men they want to be. We are clear that they are responsible for their own choices and they are the ones who need to change. Domestic abuse is still prevalent but there has been a huge change of attitude over the years in how the justice system deals with it.

In previous decades it was seen as private behaviour that went on behind closed doors. Now the police and the courts take it much more seriously and it’s rightly seen as a serious justice issue.

All those years ago sending an abuser to prison was probably the best the system had to offer in that it would have provided short-term respite to victims.

But now it’s recognised that sending a man who is behaving abusively, often because of misogynist views, to a prison full of men is very unlikely to promote positive change or rehabilitation.

If we want to change behaviour so we have fewer women being abused by their partners then it’s about smart justice and we believe the Caledonian system is the best way of achieving that.

—

Our Talking Justice blog series brings together reflections from across our society. We are committed to changing the conversation about justice, increasing understanding and support for what will make Scotland better for all of us. To that end, we have have created a resource that maps out the Scottish justice system. This has been developed into an interactive digital tool: Navigating Scotland’s Justice System.

A joined-up justice system is needed to build a safer, more equal, healthier Scotland

As part of our Talking Justice blog series, Amelia Morgan, Venture Trust CEO, explains why a joined-up justice system helps improve lives

“The life that I have now is brilliant compared to what it was like. I thought I was a failure and that I was going to die in that horrible existence of addiction, prison, violence and fear.” Stephen

“I’m in a brilliant place. I get up every day and it’s not drugs I think about. I want to go to college, I want to eat well, sleep well and be healthy. Venture Trust believed in me. They gave me the support and the drive and it’s changed my life.” Lucy

It wasn’t a prison sentence that allowed Stephen and Lucy to make a better life for themselves after getting caught up in Scotland’s criminal justice system. It was a decision to keep them out of prison. A decision that offered a second chance and an opportunity to access support to address the underlying issues that had led them to appear in front of the court.

Too often for many people, living with the constant pressure of poverty, inequality or past trauma, the impact on wellbeing and relationships leaves them isolated from their communities, feeling unable to take part in society or access the support services they need. And all too often this has a negative influence on their lives including the harm of crime.

Evidence shows short prison sentences don’t work if the aim of sending someone to prison is to rehabilitate them. They are enough to disrupt employment, medical care, housing, and family relationships, but not long enough to tackle the true causes of offending behaviour. People jailed for a few months come back out even further from finding a route out of crime than they were when they went in.

A joined-up justice system is making Scotland a safer country. This includes services such as courts, police, and social work, that work across different stages of the Scottish justice system and dovetailed with support services in health, housing, employability and education. These vital services all work together in different ways and at various stages of the justice process to tackle the underlying causes of crime – by offering treatment, rehabilitation, training and support – to prevent offending, repair lives and make Scotland a safer place to live.

At Venture Trust we are committed to community justice because we know it works better than short sentences at reducing re-offending. But to be effective it needs to be an equal partner within the framework of the Scottish justice system. Community justice needs to be resourced, be an integral part of the system that the courts can rely on when passing sentence and deliver results. Getting the right expertise in place is crucial to making the system work. This means investing in specialist providers, but also in ensuring that there is collaboration and integration between services that will ensure people get the right level of supervision and intervention.

The best way to steer someone away from crime is to empower them with the tools and skills to make better decisions and to show them that they do have a positive part to play in their community.

Building positive relationships, getting away from negative influences, getting ready to get and hold on to a job, and just believing in themselves have a huge impact on people’s desire to build a better life.

Scottish charity Venture Trust delivers intensive personal development in Scotland’s outdoors and communities – challenging people on criminal justice orders to confront the attitudes and behaviours that have led them into the justice system. It gives them the capability and motivation to leave that behind and take responsibility for building a better future for themselves and their families. Find out more: www.venturetrust.org.uk

—

Our Talking Justice blog series brings together reflections from across our society. We are committed to changing the conversation about justice, increasing understanding and support for what will make Scotland better for all of us. To that end, we have have created a resource that maps out the Scottish justice system. This has been developed into an interactive digital tool: Navigating Scotland’s Justice System.