Reflections On My Apprenticeship, Jade Kilkenny

Two years as an Apprentice with Community Justice Scotland – a place like no other. Always there for each other, it’s a caring, genuine, place to be. I will be a better me.

Starting this job, I had a totally different perception of how it would go – I thought I was going to be working in the Police by the end or getting an SVQ 2 in Justice. This apprenticeship was not like other apprenticeships; I didn’t have to complete modules and I had mentors who supported me on a professional and personal level. I got a decent wage, which is really important as people who apply for apprenticeships don’t always have family to support them. I managed my own diary and worked with a structure; this gave me responsibility and they trusted me, without doubt. I got to pick what I wanted to achieve and what teams I wanted to learn from. This apprenticeship was not just about developing professionally, it was also developing my skills for the future. Karyn (McCluskey) says all the time, I look like a different woman – and I feel like one too. I came into this job as Jade Kilkenny, not the girl who had lived trauma.

I have more than one mentor and they support me in different ways. They help me to flourish and grow, and that makes me laugh and feel good. They guided me to the right path for my future. I have been able to discover myself and learn ways to cope with trauma, and create a new way of surviving and thriving. I have developed skills and qualities that I did not think were possible. Choosing my mentors in my own time was crucial for me, not because I don’t believe they’re all wonderful people, but because I needed to discover people for myself. This made my relationships stronger. Having mentors encouraged me and pushed me to keep going, especially having lived a chaotic lifestyle and having low self-esteem.

I feel accepted. I have a designated Line Manager, but they are more than that. Their role at Community Justice Scotland does not specify that they need to be trauma-informed, but they are. From the beginning, during my interview, I knew they were special people. I connected with everyone straight away. I interviewed them, I questioned how they would support me and I was humbled by how supportive they were.

My mentors encouraged me to improve my work and monitor my progress, but they didn’t want me to just succeed, they wanted me excel – in my own time.

I have special relationships with people in the team, and these are for life now. I really struggle with trust, but as time went on I started to believe what they thought of me. I find education hard, but I realised education is not just about academic learning -the team taught me that learning is a part of life. I am able to focus and be more self-disciplined in my work. I learned how to be a professional and have belief in myself. Although initially reluctant, I understand having a routine is essential for me and this keeps me on the right path.

I choose to get up and be passionate about what I do, whereas before it was more about getting by. I value being sharp and smart because people take you seriously.

I still have improvements to make but I believe I am more than just my experiences. I believe I have skills and worth in this cruel world. I have learned what chaos looks like and where it comes from. Moving on from the past is extremely hard, but I know now it’s not the life I want to lead. I also know that some relationships are negative and can consume you – you can only control your own behaviour and reactions. Not every relationship will be healthy.

Working in a government building with high security was a new experience for me, and at the start I didn’t feel like I belonged. Sometimes I found it hard because people were dressed up, and at that time I didn’t have the confidence to believe I was worthy enough to be there. As time went on, I realised CJS was unique from other places and professionals. I was being paid to develop my skills and give my views. I was in a room with teachers, youth workers, doctors, researchers, analysts, writers, campaigners, managers, development workers, HR workers, police officers, policy workers and residential workers. I came out of my shell as days went on, and I realised it was people who just wanted to make a difference, like me. Everyone had their own journey, just like me, and people were not afraid or ashamed to show me this.

Over time as my confidence built up, I started to see my value.

In this job, I had great and unusual opportunities. I was able to go on training courses and attend events that were new to me. I learned about new technology, like electronic monitoring, and gained lots of new expertise. I have written blogs about how important education is, and I have been able to share my views about Corporate Parenting. I filmed this vlog about my role and what I have achieved. I developed my office skills so that I could contribute to the office. Sending emails is such a presumed easy task but I found this really difficult – how to confidently send a professional email. I learned about research and the importance of having various types of research which is vital for services and the people who use them. I learned how to conduct a research paper, and to use policy to influence decision making. This made me realise how much policy can influence someone’s life and relationships within services. I had the opportunity of organising a Personality Profiling training day for the whole CJS team. I came up with this training because I wanted everyone to understand each other, and we got to learn more about each other’s dos and don’ts within the working environment.

I went on to complete a qualification: Award in Education and Training. This qualification gave me more of an understanding about the preparation it takes to do successful group facilitation as well as developing my skills and confidence.

There should be apprenticeships like this everywhere because it has allowed me to develop and learn whilst creating relationships with lots of people.

CJS has allowed me to be myself, make mistakes and choose my own development with guidance. After two years, I have grown passionate about community education. That’s why when I leave, I will be going to university to study for a degree in Community Education. Being an Apprentice at CJS helped me realise what I am good at. I enjoy making a difference, and I realised I can make a difference without relying on using my past trauma.

I can make a difference being Jade Kilkenny. I am leaving my imprint, and I will be back!

“If someone has a conviction, it doesn’t mean they won’t be a good worker…

…Everyone has a past and deserves a second chance. If they have the right attitude, turn up for work on time and put in the hard graft then we will give anyone a chance.”

We speak to the JAD Joinery Ltd. team about our new campaign, smart justice in action: employability. The campaign is aimed at SMEs across Scotland. Our goal is to communicate the benefits of employing people with convictions and start to challenge some of the perceived barriers.

So, JAD Joinery tell us about your team…

Our Apprentices work harder than anyone else; they are first on site and last to leave. On their first day we give them a tool kit worth a decent amount of money, and we give them JAD clothing. We do have strict rules – 3 strikes and you’re out – but we give our boys purpose and trust and we get rewarded for it.

We have a good set up here, it’s hard work but we have fun. Our Apprentices have to meet our high standards and they are assessed on timekeeping, attitude, working with others and their commitment. We track that and each month our best apprentice wins a new tool for their kit. We also reward our apprentice of the year with a holiday for two to Ibiza – we know that a bit of healthy competition works! And, we pay decent money, more per hour than the government says we have to. Our boys work with us and over the years we give them all the skills they need to earn much more.

We aim to have 120 apprentices soon and a conviction is not going to get in the way of us giving them a chance. It’s up to them to take that chance and make something of themselves.

What does success look like?

We have seen boys come right out of their shell, gain confidence and become part of our team. We create a sense of belonging and we’re father figures to a lot of them. We are strict, but a bit of discipline and boundaries are positive. We’ve had letters from mums thanking us for turning their boys into men – and thankful that they’ve found a path, earning square money and taking pride in their work.

We don’t get any funding to do our apprentice programme – we do it because it makes good business sense, but It’s not just us that benefits, or the boys – it’s their families too. We’ve had pictures drawn by wee lassies about their dads working for us. We’re a real team here.

Do you have any advice for other employers?

What advice would I give other employers who don’t recruit people because of a conviction? I would say have you never made a mistake in your life? I would also say that’s a false economy. You have to look deeper and think beyond your prejudices. If you give a person somewhere to belong and something to lose, they’ll give you loyalty and hard work – and your business will reap the benefits.

- Find out more about our new campaign, smart justice in action: employability here.

Safety is Paramount

Last week as part of the Restorative Practice Forum Northern Ireland’s (RPFNI) 25th Anniversary Conference, I attended a workshop on whether restorative justice can be applied in cases of intimate partner violence. For my final blog of #RJWeek, I’d like to share some of the points discussed. The workshop included representation from police, probation services, restorative justice professionals, government, youth justice agencies and women’s support organisations.

From the outset it was agreed that while there were real concerns in considering whether restorative justice would ever be suitable, no agency felt they had the right to take restorative justice ‘completely off the table’. There was also consensus that any restorative justice process should only be initiated by the person harmed, and never by the perpetrator. And, that a bespoke risk assessment, with robust testing and frequent evaluation, is required. This requires multiagency information sharing and continuous input and evaluation throughout.

There were differences of opinion as to whether restorative justice could ever be used in cases of intimate partner violence, as an alternative to prosecutorial action. It was felt by some partners that, as an addition to the criminal justice process, this may support an individual harmed to achieve person-centred outcomes. A number of partners believed that it could be offered to persons harmed as an option in achieving a level of justice or resolution, where disengagement with the formal justice process was likely. This would need careful risk management.

Safety must always be the primary aim. Wrap around support was agreed to be fundamental to every potential restorative justice conference – before, during and after. The needs of all parties had to be built into that, including speech, language and communication needs, mental health and whether children are involved. The risk of exposing or perpetuating trauma was discussed at great length, and all partners felt there must be a suitable, long-term commitment from healthcare providers to work with the person harmed, the perpetrator and family members beyond addressing the harm resulting in or part of, a conference, and into the future.

There is much international debate on the use, misuse and potential veto of restorative justice in offences of intimate partner violence, and there should be in my opinion. For this to be seriously considered we must be open to taking part in often heated conversations, fuelled by incredible expertise, fear, energy, passion, mistrust and empathy. The only thing I am clear on frankly is that we should always place the safety and wishes of those we advocate for firmly at the top of our agenda. And, this means it must remain something which can be keenly explored at every opportunity.

My thanks goes to participants for their insights as part of the RPFNI 25th Anniversary Conference (2019), and in particular to Kerry Malone, Independent Social Work Consultant for hosting such a thought-provoking workshop.

A Culture of Restoration

To me, it is important to acknowledge that, as individuals, we can embody restorative values as a means to prevent harm and to address it, if it occurs. While we can formalise approaches to restorative justice, we can also ‘become more restorative’ in the way we engage with others, both personally and professionally. In addition to making us more effective restorative justice facilitators, this also has valuable benefits for people within our sector. During my work in Northern Ireland over the last eighteen months, I have been introduced to two examples of this in action. Both examples have helped me to identify the necessary values and principles needed to make this a reality.

In HMP Maghaberry in Northern Ireland, staff have been supported by restorative justice professionals to develop restorative practices. This is in response to violence and antisocial behaviour which have since reduced by 29% (April 2018). In addition to the use of conferences between people identified as ‘enemies’, restorative circles have been introduced within a wing of the prison. Prisoners and staff are encouraged to sit down together and discuss issues which they face personally, or which affect them within the prison. The circles remove any perceived hierarchy and everyone is afforded the opportunity to talk honestly, including staff. Prison Officer’s explained this had improved relationships with prisoners because they feel more able to appreciate others points of view. Prisoners were able to see staff as human beings, finding more common ground.

In Hazelwood Integrated College in North Belfast, a restorative culture is being used to bring communities together internally and from outside the school grounds. Circles are used to give students, parents and communities a voice in school decision-making, and restorative approaches are used to addressing conflicts as they arise. ‘Integration’ is no longer viewed as an attempt to blend the two sides of a conflict by Head Teacher Maire Thompson, but about achieving real equality, however this looks.

Children don’t learn from teachers they don’t like

And, Ms Thompson is clear that staff should embody restorative values as a way to draw out and encourage the talent she strongly believes every student holds. Her inspirational, restorative practice has resulted in improved attainment, attendance and opportunity.

I know there are many examples of such approaches, including within Scotland, but the most effective will be founded in the same values and principles as these. Promoting rights through equal participation; active listening with meaningful feedback; acting in the best interests of those harmed; taking a solution-focus; and truly valuing relationships. We are human beings, so we won’t always get this right, and ‘owning our mistakes’ also forms a key part of any restorative culture. This is really just treating people as we wish to be treated ourselves, to break down barriers (both real and metaphorical), and prevent conflict from taking root in our communities.

The Power of Harm

The great Tim Chapman from the University of Ulster introduced Narrative Approaches to me some time ago. And, in particular the work of Michael White who said in 2007, ‘the person is not the problem, the problem is the problem.’ When a crime is committed, the problem is not the person who committed harm, the problem is the harm itself – and the voicing of that harm has the power to change everything.

The role for restorative practice within our justice system in Scotland could not be clearer. It allows the impact of harm to be articulated and explored by those affected. That is, the person harmed, the person who commits the harm and their family, friends and community. It thereafter seeks to find a resolution that promotes responsibility, healing and moving forward against what has truly been experienced. It is personal, truthful and sincere.

On reflection, the above may form the basis for a definition of what it takes to actually address injustice, and not to simply ‘do justice’. Our current justice system in Scotland does not utilise the power of harm in its processes and conclusions, and so cannot address this for those who are impacted by it. It focusses on the perpetrator of harm, and takes a formal, procedural approach to mending ‘broken rules’. From the moment a person who has experienced harm tells their story to a Police Officer, it becomes one-dimensional, losing its power as it moves through our legal checks and balances towards its ultimate, and often untimely, resolution.In many cases, the impact of the harm will never be voiced again, and where it is, all too often the outcome achieved can never outweigh the additional impact and trauma experienced in its retelling during a criminal trial.

We cannot deny that much of our society believe that people who cause harm should be formally sanctioned within the justice system. But what can the system then do to address the real impact of harm?

I feel the answer to this lies in ensuring equitable access to restorative practices as an integral part of our justice system. Where it is no longer viewed as the alternative. This represents real community justice. Empowering people and communities by giving them a voice. Not only does this promote feelings of safety and fairness, it reduces the long-term health and wellbeing impacts caused by harm. If ‘all justice is local’, as stated by Debbie Watters from Northern Ireland Alternatives (2019), we must allow all of Scotland’s communities the opportunity to heal themselves in a meaningful way, by providing more opportunity to do so. Without that, little reintegration and citizenship can be effectively achieved.

Meet our Apprentice, Jade

My name is Jade Kilkenny. I am one year into my apprenticeship with Community Justice Scotland – with one year to go! This apprenticeship is not like any other modern apprenticeships that I’ve come across. In this job, my work is tailored around my development, building confidence, creating new experiences and relationships.

During my apprenticeship, I have enjoyed organising events. This includes arranging a Personality Profiling training session for the whole Community Justice Scotland Team. Organising this event was a huge responsibility and it helped me to develop budget and time management skills. I also get to contribute to external events. This has helped to build my confidence to speak up, and get my viewpoint across effectively and strategically.

As part of my apprenticeship, I have completed a qualification in Award in Education and Training which will provide me with the opportunity to go out and deliver training courses. I have also shadowed colleagues in other teams to learn about their role at Community Justice Scotland.

I am involved with other organisations like LANDED, The Care Review and Staf. I have learned a lot from these organisations and my apprenticeship. This will give me experience and confidence to achieve my future career goals. Watch my short film below!

Fact-finding in Finland: a search for Smart Justice

It started with a tweet.

Our Chief Executive saw a tweet from @cisweb – Children In Scotland – about their proposed study visit to Helsinki in April. Finland is often held up to be a country that Scotland aspires to. We already share some features: a similar population – 5.5million – and a challenging geography – it is the most sparsely populated country in the EU. But there are significant differences too; particularly in how they administer justice. Part of CJS’s role is to learn from best practice wherever it occurs, so we decided to find out more.

Along with around 30 people from a range of public and third sector organisations from across Scotland, Keith, head of improvement and I visited Helsinki in late April. We took part in a well-organised week of fact-finding and face-to-face meetings with a diverse range of organisations, governmental and third sector.

The programme was tailored to the needs of the delegates, who all have a professional interest in early intervention and prevention. It also gave us some time to arrange our own meetings on topics of specific interest. In our case we contacted RISE, part of the Ministry of Justice which deals with community sanctions and KELA, the state welfare body overseeing the universal basic income experiment.. Colleagues at RISE and KELA were generous both in the time they spent with us and their hospitality. If we weren’t already aware of Finland’s excellent education system, it immediately became apparent to us – all emails prior to our visit as well as the meetings themselves were held in English.

On day one of the trip, we were given an overview of the Finnish education system at the Ministry of Education and Culture. It highlighted some key features: paid maternity/paternity leave until a child is aged 3; instruction in a child’s mother tongue as well as in the 3 Finnish national languages; free access to early childhood education and care (0-5); pre-primary education (age 6) and basic education (age 7-16 in the same school to avoid a difficult transition). At age 17 students have a choice of either general upper secondary or vocational education and training. The focus is on ‘lifelong learning and no dead ends’.

Appropriately enough there was ample opportunity on the trip for the teachers attending to witness the education system in action. Strikingly, despite potentially even worse weather than Scotland, a lot of time is given to outdoor play – including venturing into neighbouring forests! When conditions are really bad the ‘Schools on the Move’ programme promotes indoor activities, including using corridors for ball games. Risk certainly doesn’t seem to feature as highly in their thinking as it does in ours! Some schools also had mini-zoos and large greenhouses to make education as hands-on as possible.

In addition to its internationally acclaimed educational attainment, Finland has a justice system focused on mediation and community sanctions; innovative social welfare experiments in areas such as universal basic income (UBI); as well as a thriving third sector engaged in the delivery of front line services.

We were particularly interested that Finland imprisons far fewer people than we do in Scotland, with fewer numbers coming into the justice system at all. The investment in early years, support for parents and families and holistic mediation services is obviously paying longer-term dividends. Even for those who do come into contact with the justice system, RISE has a stated aim of increasing the use of community sanctions . Currently around 50% of all cases they deal with are given community sanctions. Not only does RISE believe that this delivers better outcomes for the people involved and reduces reoffending, but it also costs the State much less. The average cost of a community sanction is calculated by RISE to be 15 euros per day; the average cost of a prison sentence is 170 euros a day.

The third sector in Finland is funded in a potentially controversial way; through the profits generated by gambling, which is entirely State-controlled. Always trying to find similarities with our own system, we decided that the nearest equivalent was the National Lottery. The irony of addiction services being funded by gambling money was highlighted by one of the probation officers (social workers) that we met. She mentioned that there was a gambling addictions office just a few floors above the local community sanctions office we visited. In any case it was a bit of an eye-opener to see rows of one-armed bandits and slot machines directly beside the check-outs in some of the larger supermarkets in the town. But then again, where do you buy your Lotto ticket?

The importance of working with the third sector was stressed by both the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Education & Culture. Relationships generally seemed good and there is a recognition that people often prefer to engage with non-governmental agencies. A striking example was the Helsinki Mission where they work to tackle poverty and isolation within society, including running hard-hitting campaigns encouraging kindness and active citizenship.

Helsinki Mission also provides a range of family support initiatives, a youth crisis point providing preventative advocacy with young people, and intergenerational activities including the inspirational Albert’s Living Room.

Albert’s Living Room is a meeting place for seniors and families with children and it aims to tackle social isolation of new parents and seniors. Open daily from 9.30am – 2.00pm and based on the simple premise that there are ‘never enough laps for babies’, it has trained 73 senior volunteers to work with new parents and children and has over 5000 visits a year.

The country also invests in innovative mediation services. We were so impressed by the work of the Mediation Office, which offers an impartial and free of charge mediation service wherever both parties of a dispute voluntarily seek it, catering for around 47000 people a year nationwide. Cases can be submitted by the police or the parties concerned and the mediation process is based on a restorative justice approach. 90% of those who engage in the process reach an agreement – usually an apology and/or monetary compensation and often this means no further legal action is required.

Aseman Lapset (or ‘Children of the Station’ for reasons which will become apparent) in Helsinki also provides street mediation services – a form of youth work where the young people get the opportunity to face the consequences of their actions by agreeing to sanctions with the victim. It also provides a drop-in centre in the city for young people to do their homework after school or simply to ‘hang out’. It has few rules other than be polite (they actively encourage the youngsters to say please and thank you to each other) and not to shout – recognising that many of the attendees have experienced trauma. Young people who come in under the influence of drugs or alcohol or upset in any way are encouraged to talk in confidence to the qualified staff and aren’t turned away, as may happen in other settings.

Aseman Lapset has proven really successful at diverting young people from hanging around the main railway station which had been one of their previous haunts, hence the name. The cold weather makes it difficult for them to congregate outside during winter months and lack of money means that for many alternative pursuits, such as sports or cinema outings, are not an option. It has had a particularly beneficial effect on a large shopping centre nearby, as having hundreds of young people milling around after school or at weekends was putting off shoppers from visiting it. So impressed with the initiative, the chief executive of that shopping centre is now the Chair of Aseman Lapset’s Board, She is a strong advocate of diversion work with young people promoting the social and economic benefits for the wider community.

A slight cloud was hanging over Aseman Lapset at the time of our visit as their central Helsinki location also has prime development potential. They are seeking another suitable venue within the city centre – location is everything. We wish them well.

The visit was an opportunity to witness first hand some of the services that makes Finland a by-word for progressive social initiatives and to reflect with the other Scottish delegates what we could learn from and adapt for back home. It also allowed us to reflect on the many good things that happen in Scotland and the importance of not only learning from good practice, but promoting our own. We must learn from others, always, but perhaps we should also learn to shout louder about our own successes too.

More information and photos can be found on Twitter via the hashtag #cisfinland

Rewriting Scotland’s Story

By Mairi Clare Rodgers

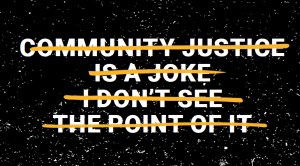

If you were at the Citizens Theatre on Friday 9 March, you might have been a bit startled when you were handed a program with this emblazoned across the front. Especially as what you were attending was organised by Community Justice Scotland.

So how did we get here? Six months or so ago, the team began discussing and debating what our big day should look like.

National conference?

Stakeholder symposium?

Annual forum?

We wanted to inspire and challenge our audience – and we weren’t inspired by any of these, so why would they be? We wanted to create something different – something unexpected. We were sure about three things. We needed incredible speakers, an inclusive audience and for the possibility of change to radiate throughout. And so, ‘Rewriting Scotland’s Story’ was born.

Byron Vincent, our host for the day, set the tone. He walked out onto the stage and told the packed theatre he was nervous. That he suffered from social anxiety. That his past had been chaotic, full of violence and addiction. And here he was; performing, making us laugh, engaging everyone in the room. ‘Write your own story’ he urged us ‘and make it a big, happy, clever middle finger to all those stereotypes’ and we were off.

Our first speaker was activist Roza Salih, one of the ‘wee lassies’ who campaigned to end the detention of child asylum seekers. When her friend, Agnesa, was detained in a dawn raid, Roza and the rest of the ‘Glasgow Girls’ got mad and got organised (it doesn’t have to be either/or). Still at school – only 15 years old – Roza engaged with politicians, the press and the public and ultimately saved her friend. But she didn’t stop there: ‘there is still suffering so, I am still campaigning’. When asked by Byron what drove her, at such a young age, to battle for Agnesa, ‘anger’ she responded ‘ and love’.

Next up was Dr Mary Hepburn, an obstetrician, gynaecologist and Scotland’s leading specialist in alcohol and drugs use in pregnancy. She established, and led for more than 25 years, a city-wide multidisciplinary reproductive health service for women with social problems; ‘services considered useful needed to be brought together in one local place’. Plus ça change. When questions were taken from the audience, a woman who was supported in pregnancy 20 years ago by Mary, spoke of how she had rewritten her story – she’s now a mentor to others who need support.

After a lunch provided by Street and Arrow, a social enterprise which hires people who’ve offended, pairing them with a mentor who supports with employment skills, debt management and relationship issues, we returned to our third speaker of the day: Professor Sir Harry Burns.

He began by telling the room he was fed up. Fed up with the lack of progress on problems that we all know about. ‘The problem is we do things to people not with people’. He urged us to disrupt, take risks and innovate ‘we can make change happen by breaking the rules’. He finished off: ‘what I’d like to see is not just a safer Scotland, I’d like to see a flourishing Scotland, where we support every citizen to realise their full potential’.

Darren McGarvey, rapper and author of Poverty Safari, followed Sir Harry Burns and echoed the same themes, issues and demands (albeit with a bit more rhythm and rhyme). Inequality, personal responsibility and experience, change, anger and love. His rendition of ‘Jump’ was electrifying: ‘and if I fall, I know you’re going to stop what you’re doing just to help me up. That’s real love.’ There’s a real spark between Darren and Byron, so the planned Q&A with the audience is abandoned as they continue their conversation – demonstrating the importance of relationships, emphatically.

Professor Jason Leitch is our final speaker. He tells us about change, what that means and how it happens – and when it doesn’t. He has the crowd in stiches as he describes his story from dentist to surgeon to faceless bureaucrat to the Citizens stage. He tells us: ‘don’t write lots of letters and reports or set-up short-life working groups – instead give the power away to actual people who use the services, change the dynamic’. His example of the parenting group in HMP Shotts which helps dads and granddads stay connected – as well as reduce the likelihood of offending – is incredibly powerful and stuns the audience.

Then, the lights are dimmed and the theatre is dark. A single spotlight illuminates the stage,

‘I stand in a toilet staring at myself in the mirror as I try to insert a needle into my jugular vein’.

A voice in the darkness begins to tell his story – a story of violence, addiction, pain, anger and then change, love, and purpose. ‘I stand here in the dark, however I shine’. The spotlight moves, and another story begins. He tells us about his experience of a terrible violent attack, the fear and trauma that followed, the inhumanity of the justice process, but also of help, support and triumph: ‘crime isn’t black and white…we’re all capable of making mistakes and we’re also all vulnerable to being a victim’. The final story begins, ‘I look at how my life was 5 years ago and I don’t even recognise the person I used to be’. She tells her story of chaos, exclusion, of battles fought, of doors slammed, opportunities lost and won. ‘I just want to be like you. I just want to go to work. Pay my bills. Pay my taxes. Eat well. Be healthy’.

She ends on a challenge:

‘Look around the room

Speak to the person next to you

Ask them their hopes and dreams for Scotland

Tell them yours

Then ask yourselves

Do they include people like me?’

Her final words may have been hard to listen to, inviting us to take a closer and more honest look at our preconceptions, beliefs and actions, but there could be no more fitting end to our inspiring, thought-provoking day. We have to speak the uncomfortable truths if we are to move forward.

This is just the beginning – our future is as yet unwritten but by listening, learning and doing we can build a smart justice system which serves every person in Scotland.

Change is possible.

Let’s talk about debt – Kim McGuigan

“Burying your head in the sand does not make you invisible, it only leads to suffocation” Wayne Gerard Trotman

Debt is a word I’ve always known. From as young as I can remember, I used to be sent to the door to tell the Provie wuman (provident loans) or Shopacheck or whoever my mum didn’t want to answer the door to that day, that she wasn’t in.

I knew it was a lie and I’m pretty sure the person on the other side of the door didn’t believe I was at home by myself.

I remember throughout my life hearing phrases like “I’m in debt up to ma eyeballs” or “I’m on the bread line” or “money doesn’t grow on trees”. As a child I didn’t know what it meant – I imagined walking by a tree that had money hanging off it – so it was no doubt inevitable that I would find myself in similar situations as an adult.

I didn’t learn how to budget money, growing up I rarely had money to feed myself and I didn’t realise that borrowing money that you couldn’t afford would never go away. I guess it was just another part of normality, growing up the way I did.

I remember when I got my flat in the high risers in the Gorbals in Glasgow after staying in hostels and homeless accommodation for years. I got a job working in a café with my cousin and I started working as an industrial cleaner for a construction company and I was making decent money for an 18-year-old. I was paying my rent and bills and I had some money left over to do me until my next wage. Looking back, I was happy, I was settled, and I had a bit of stability for the first time in my life.

It didn’t last long. After a few months of being settled I found myself in a bad relationship. He had a cocaine habit and, looking back, I don’t know how I was so stupid but I thought I loved him and so my wages went on bailing him out. I was behind on my rent and missing work because some days he wouldn’t let me out the house. My mobile phone was cut off and before I knew it I had a credit card and things quickly spiralled out of control.

I became the one burying my head in the sand, wishing my problems away. The next five years were chaotic – I drifted through life. Things went from bad to worse until at 22 I found out I was pregnant. I started to rebuild my life and applied to do a hairdressing course. I wanted so badly to be a good mum and give my child a good life. I moved into a new area and, to be honest, I never gave the debt I had stacked up another thought. My full attention was on my unborn child.

After a few years I was stable and doing well but then I ended up in another bad relationship and in trouble with the police again. I got a supervision order. But I vowed that this was the last time – that no matter what it took, I had to get help. I had to find the answers as to why I was so troubled and I had to get my arse in gear or I was going to repeat history with my child and that was not a option for me.

I finally got the help I needed, I started working and I got an education. it was then that the debt letters started coming. I knew that if I wanted a stable future for my child then I had to do something about it. So, I signed up for a trust deed and in four years’ time I will be debt free.

Well, that was the plan. In June 2017 I lost my job due to funding cuts and I fell behind on the trust deed payments. The company have been amazing; they have put a hold on the payments until I find full time work again. But it doesn’t stop the worrying, especially when I struggle to find work because of my convictions.

What I have learned is that, if you talk to people and don’t hide or run away from your problems, when you face up to the reality of what’s going on then things don’t spiral out of control. A problem shared really is a problem halved.

When I was asked to write these blogs about my experiences a friend gave me an old laptop and I had to subscribe to a Microsoft office package as I couldn’t afford to buy it – £7.99 per month. I clicked send and I was all set up and I started using the software. I was on a high, as writing has not only became therapeutic to me, but I feel as if I have found another passion of mine. I didn’t do well in school and I only learned how to use a computer at a community learning course but, regardless, I wanted to get my story out there as an example of how people can change – and if that meant that I had to budget a bit more than usual then the £7.99 was worth it.

Later that day I went to the shop and my card was declined. I panicked and when I checked my online banking I realised that Microsoft had taken ten payments of £7.99. That was nearly £80 out of my £120 a fortnight job seekers allowance. I instantly started to worry; how was I going to buy food for myself and wee boy? How was I going to pay his lunch money, pay for gas and electricity? how could I be so stupid? I was overwhelmed with worry, but I reached out to someone and they advised me to call Microsoft and thankfully I got the money back.

The point in writing this blog is that to most people £7.99 is not a lot of money. If people buy a computer then they would buy the software and not have to worry about buying cheaper food that week or cutting out items from your shopping list. I’ve became a professional at budgeting the little money I have. I constantly have “mum guilt” because I can’t get my wee boy things he wants or feel like I’m failing him because I can’t find a steady job.

Going to bed on a empty stomach is the norm for me because, before anything else, I make sure my wee boy is healthy, with a good diet and that he has warm clothes and his ever-out-grown school uniforms are replaced.

Scrimping and scraping by, it’s hard not to feel worthless at times but I don’t have another option. I won’t borrow money; I won’t be tempted by credit agreements or buy now pay later.

I do what I must do, and I know there are millions of people out here the same as me and people much worse off. It’s hard at times, but I know this isn’t forever. I know this is another chapter in my life and I know things will get better.

Turning your life around is all about learning how to live a different life to the one you were living For me, it’s not just about changing yourself and unlearning everything you once knew; it’s accepting responsibility. It’s not being scared to answer the door or open letters to find final warnings.

To me, it’s about tackling the problem there and then – pretending won’t make your life any easier nor does hiding.

Keeping hope and staying positive in hopeless situations helps and knowing that all the little steps you take today will ensure you have a better future tomorrow.

Venture Trust – investing in smart justice

Lucy spent ten years addicted to heroin. During this time she was also convicted of theft and lost her son to care. Her life had hit rock bottom.

“I was a heroin addict for about ten years and in and out of the criminal justice system. My son went to stay with my mum because I wasn’t looking after myself, and they thought I wasn’t looking after him.”

Today, speaking from the grounds of Perth College Lucy has been clean for over 2 years; at 37 she has returned to education for the first time since she left school at 15.“I’ve got a portfolio of certificates and I am aiming for a degree with a dissertation in addiction and recovery,” Lucy says. She has completed peer mentor training with Venture Trust and its partner Move On to help other women caught up in the criminal justice system.

One of Lucy’s proudest achievements was being recognised with the presentation of a local champion award through the criminal justice system. The system that could have locked her away instead provided her with the opportunity to change her life.

“My life has totally changed. I’m in a brilliant place with my son. I’ve got a fighting chance to get him home. I have my grandchildren on weekends. These are things that would never have happened before” she says.

“I get up every day and it’s not drugs I think about. I get up and I want to go to college, I want to take the dog for a walk, I want to eat well, sleep well and be healthy.”

Reflecting on her journey with Venture Trust’s Next Steps programme which is funded by the Big Lottery Fund, Lucy explains it was the three-phases of the programme all working together that allowed her to “get her life back”.

Like all of Venture Trust’s programmes, during phase 1 there is support in the participants’ communities which usually lasts for 3-6 months. An outreach worker, in partnership with other agencies, will help the participant to stabilise their lifestyle, so that they’re able to embark on (and benefit from) the wilderness phase. The participant will be introduced to other local people in similar circumstances, helping them to build a positive network of peers and supporters. Finally, the participant will receive one-to-one support to identify the choices, actions or behaviours they need to change in order to develop a more sustainable lifestyle.

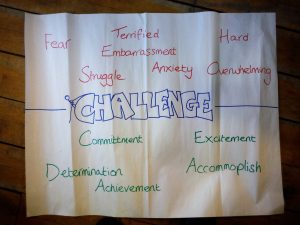

Phase 2, the wilderness journey or residential, is at the heart of Venture Trust’s programmes. This setting – far removed from a participant’s everyday environment, and often chaotic life – gives people the chance to tackle physical, emotional and social challenges. These challenges are carefully designed to encourage learning and development, to help participants to increase their aspirations, confidence and motivation, and to develop a range of skills for life, learning and work.

“We were not far from Pitlochry, but it could have been a million miles away,” Lucy says. “There were no phones and we took on challenges in the outdoors. But all of these challenges and activities were giving us tools for coping when we returned to our everyday life. Dealing with emotions and anxieties and putting into place an action plan for being back in the community.”

Back in their community during phase 3, each person has access to one-to-one support from a Venture Trust outreach worker. They are supported to achieve their aims, to utilise the skills they have acquired to work towards opportunities such as employment, education, training and volunteering.

“Venture Trust believed in me. They gave me the support and the drive and it’s changed my life,” Lucy says.

Venture Trust has two criminal justice programmes that are integral to the Scottish justice landscape. Living Wild and Next Steps. The focus is on supporting individuals to make positive changes through personal development, experiential learning and acquiring life skills. Participants are helped to raise their aspirations, confidence, understand cause and effect, and responsibility, and give them space for change. In a recent study*, evidence suggests that 75% of women who have completed the Next Steps programme are less likely to reoffend, and 83% are more employable, with a significant number already in employment. These programmes really work.

It is widely understood that prison and particularly short term sentences is not the answer to reducing offending/reoffending. It does little to address the symptoms of those offending, or to encourage reform, and many of the negative behaviours that resulted in a prison sentence, are exacerbated inside prison. Those that are sentenced to a custodial term of 6 months or less are twice as likely to reoffend than those serving a Community Payback Order (CPO).**

If community based services, and programmes are to be the alternative to custodial sentencing of 12 months or less, then these services must be appropriately developed and resourced, and evaluated to ensure efficacy. There must also be greater understanding of what is available and trust that the alternative works, amongst those giving the sentence.

CPOs are a valuable alternative to short term custodial sentencing; they benefit the wellbeing of the individual, and the wider community, the tax payer, and encourage a safer environment. Authorities must work closely with organisations like Venture Trust in order to get the best results.

The opportunity now exists to start getting this right; to start making justice work. It is time to invest in smart justice.

For more information about Venture Trust, please visit their website: http://www.venturetrust.org.uk/

*Dr Shelia Inglis, SMCI Associates

**Community Justice Authorities consultation

By

By