An Ode to Resilience – Karyn McCluskey

I read Kim’s blog a few days ago, and I thought I would just write a small addition. Many will think it is neither here nor there, but comes back to the subject of resilience. I talk about resilience all the time, resilience in leadership, lack of resilience in many of our most traumatised citizens, the surprising level of resilience in so many of our citizens where we would expect there to be little…so I go on about it at length.

The day Kim went to her interview on that rainy day in late December, I phoned her, by chance. It was around 5pm and she was in Glasgow City Centre.

It was dark and she was alone and when she answered the phone all I could hear was deep, wracking sobs, the sound of absolute despair. The sobs came from the depth of her being.

Many of us will have experienced that sort of emotion in bereavement or the catastrophic events that can turn your life upside down. If you are reading this, and are taken back to that time in your own life, then you will know the sort of sobs I am referring to. It took 40 minutes to get what had happened out of her. I wondered how quickly I could drive from Edinburgh to Glasgow in rush hour to take her home, to comfort her, and the answer was too long. Kim doesn’t have the support networks that so many of us have and which wraps around us at these sort of times. It’s a lonely path that she is walking.

She wasn’t any better the next day, full of questions about when she will have repaid her debt; when she is allowed to move on; when is enough, enough? My platitudes about time, resilience and determination and that ‘her time will come’ were weak and no comfort at all – for in truth there are systemic and societal norms that are designed to keep Kim in stasis, doing nothing to really integrate her back into society and letting her participate fully. What a task that is – just imagine the weight of that on your shoulders, realising that to move forward there is a huge amount of things you have to shift at the same time. It’s like Sisyphus and the boulder

My blog isn’t really about all the things that should change or the transformation in society that is required. It’s about resilience, because three days later Kim had re-centred herself, picked herself up and refocused her attention on where she wanted to go.

There was no licking of wounds, feeling sorry for herself or bemoaning the inequality she finds herself at the mercy of.

This is what I want to write about.

The phenomenal levels of resilience that some people have, despite the best efforts of society to grind it down. If I could extract the essence of this from Kim and others, we could achieve anything, for she on her own has epitomised to me what resilience is, what drive looks like, what absolute determination looks like despite all the things designed to keep her where she is. She is back pushing the boulder up that hill, but now she has more people helping her push it. So thank you, all those out there that offered their support, changed their processes off the back of her blog, and promised themselves that they would help change it.

This is how transformation happens

To the people who don’t see me, but see my convictions – Kim McGuigan

I am writing this because tonight I signed up with a recruitment agency. My interview was going well, until it got to disclosing my convictions. As always, I was open and honest about my past mistakes. It’s the only way I know how to be.

I handed over my most recent disclosure and – by the way – it clearly states that I am not barred from working with any type of person. That means that I pose no risk to the people that I would work with. The information that seems to have the biggest impact on employers, and others in authority, is from when I was 17 years old, more than a decade ago. It is a racial conviction, one that I am deeply ashamed by and of. It happened in 2004 – by the time I went to court and was convicted, it was 2005.

Anyway, back to tonight. I told the woman the circumstances around the conviction – which by no means excuses it – but I was living in homeless accommodation and I had been sofa-surfing since I was 14 years old after my family broke down.

That didn’t seem to be enough for this woman.

She wanted to know more about my life.

I froze, I wanted to get up and say ‘F**K this’. I wanted to say that she didn’t know what I went through, but instead I sat there and let her give me a lecture on risk and how I needed to be risk-assessed. I repeated ‘but I was 17!’ but it was like she didn’t hear me. She started to type up a report for my file that read….

I believe Kim will not be a risk to any service user and deserves an opportunity to turn her life around!

‘Risk’ I thought to myself, ‘how am I a risk? I am a mother and a damn good one at that!’. Sure, I’ve made mistakes, but I’ve learned from them. I have done the work on myself, I’ve spent the last five years healing and recovering from wounds and repairing the damage I’ve caused to others and myself.

I did that sentence 12 years ago, why am I still being punished?

Why do I still have to justify and explain events that take me back to the night of that conviction? Why do I have to revisit the trauma? When am I going to be free from my past?

Why am I not allowed to move on?

As soon as I get somewhere in life and try to better my future for me and my wee boy, this conviction haunts me and I’m right back there. She then went on to ask me about my relationship with my parents and why I was homeless, to which I answered that I didn’t have any contact with them now. Did she want the truth? Would it have made a difference? Why do I have to continue to spill my experiences when I’ve worked so hard to turn my life around? I already have, by the way….

Did she want to hear about when I was 14 and my dad had an affair with my mum’s pal who stayed upstairs from our flat? That my dad left and would walk by me going up the stairs to his new family? Did she want to hear that my mum tried to take her own life and I found her and had to resuscitate her? That the reason I became homeless was because I’d go home steaming drunk, so angry that she would do that while I was in the house sleeping, that I’d pick fights with her after she got out the hospital so she kicked me out?

Did she want to know about all the horrible things I witnessed while staying in the Queen’s Park Hotel? The place where the authorities I went to for help put me, but which led me to be even more vulnerable. That I ended up in a violent relationship that nearly left me dead.

Did she want to know that when I found the strength to get out of that relationship, I went on a bender all weekend? That eventually this ended up with me in a restaurant, in a fight, that led me to getting that conviction that has haunted me ever since.

That every time I think I’ve finally been able to prove that I have changed, someone questions me about that conviction and treats me like I am ‘a risk’ when all I want to do is work and help people.

Did she want to know that those experiences were only my teenage years – did I have to go into my childhood as well?

I think I’ve shared enough.

My point in writing this is that I don’t understand why I am seen a s a risk for something I did when I was a stupid wee girl. I nearly had my education ripped away from me because of that conviction. I fought it and I’ve worked so hard the last four years to make life better for me and my son. I am so tired of having to explain myself, to be sitting feeling that shame and embarrassment. I am not that person anymore. I am just a mother who is simply trying her best to give her son the life she never had. And I am doing a good job. Why can’t I just be that person? When will the stigma and labels ever leave me? When will I finally complete this sentence and be free?

I really don’t know what else I can do.

So, I’m just going to keep doing what I have been doing. I’m going to keep getting better and work a little harder and just hope one day I can go for a job or go into education and not have to explain something I’ve tried to move on from.

You see, it’s not just the conviction, its everything that led up to that conviction I must relive over and over and over. All I want to be is me.

Just see me.

Don’t judge me, don’t force me to spill my life story because you can’t understand that it was 12 years ago.

I’m not a risk to anyone, I’m just me.

Sentenced to Change – Kim McGuigan

I had attended an event called ‘Communicating Justice’ organised by the Scottish Universities Insight Institute. I had shared my story with the audience about when I received a community sentence and the sheriff who I felt had played a part in turning my life around.

I was given a two-year supervision order and the judge had me back in court every few weeks to monitor my progress and assess reports from my social worker. I was originally told by a sheriff that I was facing a custodial sentence – I believe I got lucky on the day of sentencing, because I ended up with a new sheriff who spoke to me. It was the first time I had been in court and a sheriff had ever asked me anything. At the time my life was so chaotic I really didn’t care and I wanted to go to prison, as I thought that was the answer to my problems.

The sheriff told me she was willing to give me a chance to address my underlying issues and sort my life out. After a few months on my order, I eventually gave in to the changes I desperately had to make and I don’t even recognise that person anymore. I got the help and support I needed and I believe that supervision was the first step that saved my life.

At that same event I was introduced to Sheriff Wood, who is one of the sheriffs in the Glasgow Drug Court.

The drug court is where people who are offending and have substance misuse issues are given the opportunity to address it with treatment, reinforced by a Drug Treatment Testing Order (DTTO) rather than prison – allowing them to become drug-free and encouraging them to commit to changing their lives.

Sherriff Wood told me that the people he sees are given intense support and various workers from many professions are available to help them reduce their drug misuse. The offending behaviour normally take care of itself when the person is supported to recover from addiction.

I was invited to go and sit in the court a couple days later. As I went through security and down to the basement, I was stopped by two guards who asked if I was lost. I told them I was going to the drug court and that I had been invited to sit in by Sheriff Wood. One of the men said ‘I’ll show you where the restaurant is pal, because you won’t be wanting to hang about, waiting with that lot’ pointing to a group of guys waiting to go into the drug court. I was quite taken aback and I replied ‘what, hang about wae they people?’ and I walked over and sat beside them.

As I sat reeling by what the security guard had just said, a man in his early forties sat beside me and started chatting away. He told me that he was feeling nervous, as he didn’t have the best results for Sheriff Wood and that he was struggling because of his homeless situation to keep up his appointments.

He said he’d be better off in the jail, but he didn’t want to let Sheriff Wood down because he had really believed in him when he’d never believed in himself.

I knew what that felt like, so I told him a bit about me and how I turned my life around and soon everyone in the waiting room was sharing their stories.

The court got called and I sat up the back, not sure what to expect, but after listening to the people in the waiting room I was excited to have the opportunity to see how the court ran. It was a strange atmosphere, waiting on Sheriff Wood coming out – you could feel the nerves from people who were waiting to go up.

First up was a graduation! The man was in his forties and had long battled with drug misuse. Sheriff Wood congratulated him, praised his hard work and told him he understood how hard that order was for him, and then the guy spoke about all the support he’d had and thanked everyone who had helped him. Sheriff Wood then came down from the bench and met the man in the middle and they shook hands as Sheriff Wood handed the guy a certificate. The room erupted with clapping and cheering, it was an experience I will never forget. I wanted to get up and give the guy a cuddle, he had tears of joy running down his face. The atmosphere in the room instantly changed and I could hear people saying things like ‘I hope that’s me next year’ and ‘aw I canny wait till I’m there’.

The next few people up were people who were doing well on their orders. They were congratulated and told to keep up the good work – I watched in awe as Sheriff Wood took his time with each person and was even joking with them. A young guy’s girlfriend had just had a baby and Sheriff Wood shared a personal story with him about becoming a granddad. The guy and Sheriff Wood agreed that his commitment to change will mean the baby will have a good outcome in life.

I was blown away with the compassion Sheriff Wood had and the way the men and woman engaged with him. But at the same time Sheriff Wood was no pushover. He knew if someone was at it – there was no fooling him. I think the court works so well because it’s up to the person to be open and transparent about their recovery and they must make the first steps to do so. They must accept the changes they have to make – the team around them, and Sheriff Wood, are there to make sure that the support is in place for them to do so.

The thing that really struck me the most was the respect the people had for Sheriff Wood. Most of them didn’t want to let him down because of the relationship he had built with them. People on DTTOs knew how hard their journey was going to be, but they became dedicated to change because they were given the chance to.

Being sentenced to change should be at the heart of the Scottish courts.

I’m not taking away the fact that people need to be punished, because laws are there for a reason. But what if there were more sheriffs like Sheriff Wood and more drug courts and more resources to help people?

Changing your life around and walking away from a life that you have always known is a sentence in itself. Committing to change takes real strength and Sheriff Wood gets that. He wants the people that walk into his court to have better lives and he believes they will. That’s the first step in change – having someone that believes in you when you don’t believe in yourself.

Our Community

Whether in your own home, for your friends or in your community is there anything more festive than trying to do good things for others? Perhaps it’s volunteering time or, as I experience in my role, those who constantly strive to make changes for people who won’t experience life fairly, fuelled by a sense of social justice.

In October this year, local authority Community Planning Partnerships (CPPs) released their Local Outcome Improvement Plans (LOIPs), as required under the new Community Empowerment Act 2015. These plans must demonstrate a clear, evidence-based, robust and strong understanding of local needs, circumstances and aspirations. The Act also places a duty on CPPs to engage with local community bodies, and to create plans for localities or neighbourhoods experiencing inequalities, and address this in a targeted and effective way.

There are lots of these locality or neighbourhood plans in Scotland. I was afforded the opportunity to contribute my views on those covering Fife, the area I live in. I welcomed this because, as my mum always says, ‘if you don’t engage, you can’t complain.’ However, what interested me most about this new way of working from a justice perspective was the definition of ‘locality’ given by the Scottish Government in the Act:

‘The CPP should also fulfil this duty for those communities which are not neighbourhoods, where they experience disadvantage on outcomes. This includes communities of interest, (e.g. young people leaving care; vulnerable adults; those with protected characteristics such as disabled people; or people from black and minority ethnic communities.) and specific households facing particular disadvantage’.

Across the community justice landscape we work with communities experiencing ‘disadvantage on outcomes’ every day. Their experience of inequality is in itself unequal, because of the additional needs and circumstances they encounter:

- Mental health needs akin to those found within a psychiatric unit.

- 21% in treatment for drug misuse.

- One in ten people having difficulties with reading, writing and numbers.

- 61% having children of their own, and 16% having experience of being in care at the age of 16 years old.

- 40% drinking alcohol aged 12 or under for the first time.

- 42% suspended from school.

- 80% witnessing violence in their neighbourhoods.

- 14% experiencing physical abuse, 10% experiencing sexual abuse, 36% suffering a head injury and 38% experiencing something which scarred them so much it stayed with them for years.

- 90% experiencing the death of a family member and 77% experiencing a traumatic bereavement.

- 42% with parents who had been to prison.

- 18% witnessing physical harm between their parents.

This is our ‘community of interest’. If this is the make-up of that community – a staggering picture of vulnerability – could we apply a locality plan to address the needs of this group? To consider this another way; could we apply a community plan to the justice places in which we bring these people together? Why don’t we?

Try to imagine if the prison within your local area wasn’t a gated community (how grand). If the people residing there were simply another neighbourhood in your town or city, with which you had regular interactions.

If this community existed, as the neighbourhoods we more readily recognise do, there would be a demand from the public, the media and elected officials to address these needs and a concentrated level of resource directed across partner services to meeting them. People from this community would be prioritised for support, they would have services on their doorsteps and we would take a preventative approach to working with their children and families as a priority – because we know the generational impact such experience of inequality can have.

But right now, we don’t. Don’t get me wrong, there is a huge amount of excellent work happening for people with lived experience and their families, but it is often hidden and does not generate the same media and public attention that tackling inequalities for other groups can receive.

Is this fair because people in our justice places have offended against communities?

That is one view, but we know if we don’t address these needs there will be more offending, and we also know we cannot condemn their children to the same multiple and complex disadvantage.

I know this might appear controversial but it’s really just a blog about good planning for a local community that needs a high level of targeted support to change their trajectory. You are perhaps also thinking that our justice places are full of people from lots of local authority areas and that they do not ‘belong’ in one area’s locality plan, but I feel that is contradictory to what the Act suggests in its definition of ‘community.’

The take home message here is if you can’t plan around these places and face your communities and services towards them then you must reach in, and take your own people back with a care package that improves wellbeing, one person at a time. Be the first locality authority that recognises the inequality of inequality, and action reintegration as a priority within your locality plans.

Why me? The value of Restorative Justice

Author: Lucy Jaffe, Director, Why Me?

People who become victims of crime often ask ‘why me?’ ‘why my house?’ ‘why my family?’. Those questions often go unanswered and victims are left feeling traumatised and sidelined. The criminal justice process is focused, for the large part, on catching and punishing the offender, not on rehabilitating victims.

Restorative Justice can offer a solution. It is a simple and voluntary process which gives victims a voice and a space to tell the offender about the impact of the crime they have committed. There are three main questions: what has happened, who has been affected and what can be done to put things right.

Let me tell you a story. One day in 2002, when Will Riley returned home, he found Peter Woolf burgling his home. He confronted him, the two men fought and Will was left with a bleeding head and the overwhelming feeling that he could not protect his home or his young family. Peter was apprehended and sentenced to a few more years in prison to add to his career criminal history. Will next met Peter in a Restorative Justice meeting in a prison cell. Both men had been prepared and supported by a trained facilitator, who ran the meeting. Will got his questions answered and his peace of mind; Peter realised for the first time the impact of his actions, has not committed a crime since that day and works with Why me? to promote RJ in Britain and internationally. The Woolf Within is a gripping 10 minute film in which Peter and Will tell their story.

The power and potential for RJ to give victims back control over their lives is immense.

It can be used for any crime committed at any time. Rosalyn tells her story about being raped by a stranger and then going on to meet him in a Restorative Justice meeting. She made an informed choice about the meeting and it has transformed her life. Why me? help many victims to get access to RJ, who have been blocked and prevented from doing so by well-meaning or over-worked professionals. Time and time again, their feedback is overwhelmingly positive when they do manage to access RJ – “I went from being a victim to a victor after meeting him,” said one woman who was attacked by her ex-partner. 85% of victims stated they were satisfied following an RJ meeting according to Home Office randomised control trials. More recent returns from Police and Crime Commissioners in England and Wales show satisfaction ratings of up to 100%.

The beauty of RJ is that it not only helps victims get answers, it is also proven to reduce reoffending between 14-27%, which can only be good for communities, preventing more people becoming victims in the future.

RJ requires political leadership through clear policy guidelines, ministerial support and action plans; it requires understanding from professionals about what RJ is and how it works; the benefits for victims need to be promoted; and finally, the myth that it is a soft option for offenders has to be eliminated.

We welcome Community Justice Scotland’s support for restorative justice and will work to ensure that the restorative offer is made to all victims of crime and that RJ is accessible to victims when and where they want it.

Keith Gardner: “Would you like a coffee, fatty?”

An odd and somewhat pejorative question, I think you will agree? It is all about context…

A few years ago, I was out for a meal with Lynn, my wife, and at the end of the hearty three courses she asked me the question above.

Whilst I acknowledge a degree of rotundness to my physique, my vanity gene became activated as did my sense of indignation at such as slur. On seeing my huffy demeanour Lynn asked: “”what did you think I asked?” – I restated the above with my best injured party face. She replied, “No, I asked would you like a café latte…“

Being deaf has its moments, some funny, some not-so-much.

One in six people in the UK have a hearing problem (all of which are by degree and impact) – however, most people do not. In my life I have been fortunate to have a really supportive family (notwithstanding the above!), really supportive employers & colleagues and am blessed with a less than shy and retiring attitude: I am no shrinking violet.

Most of the time my disability does not hold me back, but it only takes a buzzer-entry system or a crappy PA announcement or a TV programme with no subtitles or an unannounced video-conference at a meeting or missing the hilarious one-liner while trying to socialise to instantly set me apart from the world of the hearing. In such circumstances this is where I become the other, the different, the alien, the alone, the anxious, the scared…the term I seek is, actually, the excluded.

Let me be absolutely clear here, this is NOT a plea for sympathy – I neither solicit nor want your “awwww-ness” or “isn’t that a wee shame”– I am simply stating the facts of having a disability. This is about inclusion.

A quote is attributed to Helen Keller (who was herself both blind and deaf): “Blindness cuts us off from things, but deafness cuts us off from people”. We can all live without ‘things’ (even a good café latte), but none of us can live without people. In a one-to-one setting in a quiet environment I, in the main, have no great problems hearing, listening and communicating with someone. If I need to constantly ask people to repeat themselves (as I have not heard them) they switch off: communication terminated. However, when I tell people I am deaf the most common response is: “Really? I would never have guessed”. This means a few things:

1. My disability is, largely, hidden (completely deaf on one side and wear a very powerful hearing aid on the other) – so unless a disability hits you square in the face (or you ‘guess’) all is assumed to be ‘OK’.

2. I am, sometimes, hard to communicate with and, as my deafness is ‘hidden’, most people give up after a few goes.

3. Over use of assumption and under use of effort – we are all guilty of this.

So now you feel a bit awkward or bad about not taking account of the needs of someone with a disability: don’t!!

Do something about it.

First, recognise that people need people and that inclusion is a state of being – it is not something you ‘do’.

Second, inclusion is about, well, being inclusive – anything that excludes has to be challenged: what you do not condemn you condone!

Third, recognise that access is a first principle of inclusion. Pause on that word “access”; the dictionary defines this as an act of allowing entry – so who is doing the allowing or not as the case may be? Awareness leads to understanding, and understanding is the first step to positive change.

With positive change we can make any possibility into a reality!

Finally, sometimes you need to work really hard to be inclusive – and not all forms of disability are obvious – and for disability read exclusion.

Whilst these days, the only purpose of my (completely deaf) left ear is to ensure my specs stay on my face, it is my ear and I am quite attached to it – it is part of me – it, by no means, defines me but I cannot (and don’t want to) deny that it is a part of what makes me who I am.

So, if any of this chimes or resonates with you perhaps you and I can go for a coffee some time – but it would need to be a skinny latte…

Nina Rogers: ‘When is risk not a risk?’

Lately, I’ve been thinking about how we view risk. At recent trip to the St Giles Trust down in London I witnessed their pragmatic and seemingly winning formula on how they deal with risk and it’s clarified some things for me.

First, we live in a world that is dominated by fear, whether it’s health and safety (don’t get me wrong, that does have its place) or whether it’s about how we – the public, services, organisations and especially the public sector – put so much red tape around processes that we forget why we were doing it in the first place. We use risk to the detriment of achieving connections – basically it stops us getting things done!

Secondly, I think our ideas about risk are confused. I wonder what would happen if we turned our thinking about risk on its head? Instead of looking at why it’s a risk to employ people with lived experience or previous convictions, what about thinking of the risk involved in not employing those same individuals?

Who is best placed to build trust and relationships, to have understanding and compassion, and who could identify and offer tried and tested methods of personal growth? My answer would be someone who has experienced first-hand what it feels like to be where they are now.

St Giles are one of the many advocates of employing people with lived experience – and they walk the walk. They recruit predominantly people with lived experience to work as Peer Advisors. We were lucky enough to meet some of the team, and they described having an instant connection with people that other support services have been struggling to connect with for months. Why? Because they talk the same language, share the same experiences and understand the same challenges. In short, they relate! These Peer Advisors are so critical to the work St Giles Trust do; their passion and drive is focused on helping others turn off the path of offending behaviour -just as they have done. The young people they support get a person they can trust, look up to, learn from, and someone who will be their advocate in dealing with services and bridge the gap between social work, housing, court and benefits agencies. The Peer Advisors can communicate on a level that speaks to both individuals and services – this is why they are so successful. So connected.

This is fantastic work – but it saddens me that we need a third party to make those critical connections between services and people. Public services should represent the communities they serve, whether that be disability, race, religion, social background or previous convictions.

If we work directly or indirectly to support the public we need to know what the public want and need, not just what we think they need. Let’s be real for a moment; if you have never been in prison you don’t know what it is like to be confined to a cell, if you have never faced a children’s panel, a court room, a housing officer, a sheriff, a police officer, a gang, violence, hunger, rejection, neglect, then you don’t truly know what that feels like. And while there are hundreds of fantastic and talented people with real compassion and empathy working in the sector, without the voice of lived experience in there too we risk getting it wrong – even with the best of intentions.

“So here is my take on risk. I think it is a risk not to listen to those affected by the justice system when creating justice policies; I think it is a risk to brush aside or downplay the immense value that lived experience can bring to the public sector; I think there is a huge risk in excluding people; and I think there is a massive risk in failing to make human connections between services and people.”

So if you are recruiting and you come across a person who has a conviction, a history and some lived experience don’t just look at what they have been convicted for and see risk. Look at their journey from that place to where they are now. Think about the barriers they must have faced, the hurdles they have jumped and the determination, commitment and resilience they must have to be in front of you asking for a job.

Then look at your organisation and ask yourself is dismissing them out of hand a risk you can afford to take?

Community sentencing works… I’m living proof!

In March 2013, I was sentenced to a two-year supervision order (probation) and a deferred sentence for two years. It was the beginning of my journey into the person and, more importantly for my wee boy’s development, the mother I am now. I look at how my life was four years ago and I don’t even recognise the person I used to be. I was expecting a custodial sentence, I prayed and prayed that I would be sent to prison, I really thought that prison was my only option at the time to escape all my problems. I was in a toxic relationship; my life was chaotic. I know now if I had gone to prison I would not be sitting here today.

It took me a couple of months after receiving my supervision to finally give in to the changes I desperately had to make. I didn’t connect with my first worker – I often felt she was trying to tell me how I was feeling or treating me like a case study. I ended up with a new worker and that’s when things really started to get better. I felt like I mattered, I felt heard for the first time in my life. She didn’t judge me, she didn’t force me to talk she just spoke to me like a person. She understood how hard it was for me.

I felt really isolated because I had to cut myself off from all my friends. I had locked myself away in the house for months whilst I did the supervision work. The first block of supervision was understanding my emotions and how my emotions affected other people. I did cognitive behaviour therapy and anger management where I worked on assertiveness. I looked at my offending and I learned something new about myself every day.

After about 8 months of supervision I was feeling positive about life, but I felt that supervision wasn’t enough for me. It was then I sought out other support. I attended a woman’s hub in my area for a while. It was good as it got me out the house and from there I started a community learning course.

I volunteered with Positive Prisons, Positive Futures who are a charity for people with convictions. It was good to be around people who were in the same boat as you. I got so much out of volunteering with them and met loads of people who were trying to make things better for people with an offending background.

I engaged with the Violence Reduction Unit and I got a mentor. He was also someone with lived experience. He got me and he understood me more than anyone I had spoken to before. My mentor helped me address underlying issues I had from my childhood and helped me to love myself and believe that I was worthy of the second chance I had. The support from him was enormous in my journey of change. Support that, if I need it to this day, is still there. He is there when I need him and, more importantly, I gained a great friend.

After two years on supervision I completed my order and since then I have achieved more than I ever thought I could. In 2016 I graduated with an HNC in working with communities and I have successfully gained employment as a young person’s project worker.

With the reconviction rate now at an 18 year low and Scottish Government’s plans to keep people out of prison and reduce re-offending further, the public need to accept the evidence that community sentencing works. I realise that there are not enough “success stories” going about and that this means some people are unaware how important it is to include, and not further exclude, those who have committed offences.

When I read about ‘soft touch Scotland’ it makes me feel like I will never be allowed to leave my mistakes in the past. That despite being a mother, a student and youth worker, that I will also be ‘an offender’ first.

I am all for backing the Government’s plans; things do need to change. People need to understand that community sentencing is about making things better – not only those who have offended, but for all of us. Most of those serving repeated short term sentences are people that, with the right support and opportunities, can not only break the cycle of offending and put the brakes on the revolving door but also go on to contribute to society too. Which means that not only do they succeed in life but their children will too. I know because I have lived it and I have turned my life around – and it all began with a community sentence.

I completed my sentence and I now have something to offer society. I believe I am a great example because I know that if we don’t throw people away, but create opportunities for them, they can change too. Before receiving a community order, I was stuck. All I needed was a support network and time to heal wounds from my Adverse Childhood Experiences. I needed guidance and role models and I would have never found any of this support if not for being sentenced to a supervision order.

I have been able to address my offending behaviour and I have not committed another offence. I have a happy wee boy who is doing amazing in school and life. I broke the cycle I was born into. And If I can turn my life around then so can anyone. We all deserve the chance to change, is that not what the whole point of rehabilitation is?

Since I finished college and got a job I feel proud, I feel confident, I feel like a person, a proper person. I feel part of my community and I feel like I belong. I am worthy, I am important and I have the right to live a life free of labels, stigma and shame. I had the opportunity to change my life around, I did my sentence in the community and I’ve never looked back. None of it would have happened if I had been sent to prison.

That community order saved my life and gave me the chance to make life good for my wee boy.

‘The Place’ to be?

Gemma Fraser, Improvement Lead, on community engagement and the Place Standard tool.

These past few months, I have been reading all the Community Justice Outcome Improvement Plans from across Scotland. But please don’t feel sorry for me, there is a huge amount of creative and supportive activity happening in every corner of the country that seeks to prevent offending and reduce further offending the panacea!). This is primarily through addressing the multiple and complex needs of people with offending backgrounds, their families and those harmed by crime, within our diverse but connected communities. I can honestly say, it’s all happening! We can be immensely proud of such progress towards change, in my humble opinion.

While reading the plans, I was particularly struck by the level of engagement carried out with those impacted by our justice process. This ranged from focus groups with those completing Community Payback Orders or serving custodial sentences, to one-to-one interviews with the victims of crimes and their families. It is obvious from this that people with lived experience best understand the issues posed by offending and the justice process. They have very clear views and, more often, smart solutions as to how we can improve things. Using these findings correctly can reduce our prison populations, providing sustainable community alternatives and a better future for generations to come.

How do we harness this engagement to create change? This fits in nicely with my work in Community Justice Scotland, where we seek to identify improvement opportunities; ways that we can capture real-life experience and apply analytical tools to improve services and the experiences of the people that use them. Handy really.

I have spent a large part of my career working across Local Authority community planning. While this has been largely strategic in nature (where at times my report-writing was the biggest strategic risk), I have been fortunate enough to work with local projects aimed at understanding communities, how they want to participate, and what ‘co-production’ and ‘co-design’ can mean beyond the latest buzz words.

An example of this is the Place Standard tool.

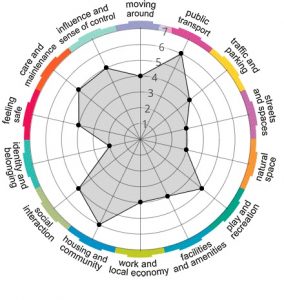

‘The Place Standard tool lets communities, public agencies, voluntary groups and others find those aspects of a place that need to be targeted to improve people’s health,

wellbeing and quality of life’

The tool considers both the social and physical environment, allowing those experiencing it to structure conversations about place and community. Fourteen questions are asked and scored between one and seven:one meaning room for improvement and seven meaning little improvement is required. Responses are plotted on the diagram, with those areas nearest the centre requiring most attention

When I place this tool in a community justice context, I can quickly identify a number of ‘places’ associated with the justice process that – while effective in their delivery – often concern the communities that use them:Nerve-wracking police custody facilities; intimidating Sheriff Court buildings; intimate social work settings ;and vast prison establishments. While the Place model could be applied to considering improvements in all these facilities, some questions would require alteration to better reflect outcomes and what communities felt they needed from them. This would move us beyond a cycle of justice interactions which, to my mind, don’t yet represent a ‘system’ of connected parts.

So how would a justice organisation engage their communities in completing a Place Standard exercise? Particularly when we know these communities are often already disengaged or not regular consulted on the ‘bigger issues’? I know we ask, but how do we show we care? The key appears to be in the provision of meaningful feedback and a true role for them in the end product.

True to form, my example of such engagement lies in Fife, The Youth Charrette. In July 2016, Fife Council facilitated a group of local young people from Glenrothes to review their town centre and consider its future. After establishing their initial views of it (largely based on them leaving it as soon as a bus arrives), and explaining the Place Standard Tool, young people were taken into the environment to consider the questions posed by the framework. The event culminated in a collective Place diagram and additional notes against each question. Young people were then asked to consider how improvements might be made and formal recommendations were presented to Council management – many of which were adopted and fed back to the group.

It is possible to take people with lived experience; those harmed by crime; families ;and partner services into places across the justice process in a similar way. There is an additional benefit to this too: it takes down the barriers felt by these groups and serves to address some of the common misunderstandings about how our justice process and its places operate. Get your local media involved!

I have always understood the reasons for positioning local community justice partnerships in a wider community planning context. For me, it is in part the ability to take advantage of tried and tested community engagement models like the Place Standard Tool. The Community Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 requires us to engage, but does leave us with a choice about how meaningful this needs to be and the means for achieving that. Good practice is everywhere and this will allow a clear feed from people using justice places into the person-centred outcomes we seek to achieve on their behalf. And I don’t believe there is anything tokenistic about that!

Why Mentoring Matters

After deciding to find out more about what mentoring meant in a Community Justice context, I genuinely had no expectations going in. Though to be fair, with the beauty of hindsight, I envision I would have been way off anyway.

Fundamentally, and unsurprisingly, mentoring boils down to the core aspect of any lasting and meaningful relationship between two people – trust. Despite all the anecdotes and witticisms about interactions between mentor and mentee, the central pillar to every successful journey remains the same, the trust between two individuals.

“I trust her, I can speak to her about everything”

Does this trust develop instantly? Of course not, in some cases it takes months of painstaking (and often unreciprocated) hard work. However, all the mentors I’ve had the pleasure of spending time with can often recall the moment in which it finally clicks. This may be an individual beginning to open up and share their story, or as simple as someone asking for help.

The conversations I’ve been involved in have had more variance than I could ever imagine, moving seamlessly from listening to descriptions of appalling adverse childhood experiences to discussing chess moves and baking muffins – seriously! People were so ready to open up to me and tell me their story, I felt moved by their openness. What also truly stirred me was the level of introspection and self-reflection individuals showed – potentially the general population could learn something from that(I say somewhat tongue in cheek).

“Sometimes it’s just a cup of tea, but I needed it”

Over the last couple of months, I’ve met with service providers and users in the community, in prison and even been present at a gate liberation. For clarity, this is when an individual is picked up by their mentor at the gate on the day they are released from prison. After this, based on the person’s support plan, they are helped with benefit applications, aided in sourcing accommodation and accompanied to other agencies who can provide additional, specialist support.

From my own experience of liberation day – understanding that this comes with the caveat that not all go as smoothly or are as complemented by optimism – it re-iterated to me the opportunity for a new start, though this time with the foundations in place to actually begin again, coupled with the support from an individual who genuinely wants them to succeed. It is impossible not to develop a relationship with someone after spending time with them and learning about their trauma. So it should be of no surprise that as I left the temporary accommodation, I asked to be updated on their journey as it proceeds. There will undoubtedly be failures as well as successes, and a whole range of emotions, but they at least can count on one thing; the unwavering support of their mentor. As mentors often told me, their phones are never off.

“I feel a bit like a jigsaw builder, putting all the pieces in place to empower them to support themselves”

*Thanks to Joe, Louise and the Wise Group.